“Wild Mary”

The Story of a Maryland Railroad

by Richard D. L. Fulton

“Wild Mary” began “her” life as the Baltimore, Carroll, and Frederick Railroad in 1852, but soon thereafter, in 1853, was renamed the Western Maryland Railroad Company (which would eventually become the Western Maryland Railway).

“Wild Mary” apparently became a “pet name” for the Western Maryland, in reference to the highly scenic, but sometimes treacherous, terrain(s) encountered. As the railway was constructed, it grew from serving the outskirts of Baltimore to blazing a trail through the Allegheny Mountains.

Western Maryland Railroad Company (WMRRC) was originally conceived to provide for the transportation of agricultural goods between Washington County and the Monocacy River to Baltimore.

However, from this original, humble conception, the railroad grew into one of the major freight haulers in the Mid-Atlantic and beyond—especially and particularly with regard to coal.

The Early Years

According to American-rails.com, the WMRRC acquired a section from the pre-existing, former Baltimore & Susquehanna Railroad, which thereby allowed the railroad company to run a service from Calvert Station to Owings Mills.

According to alphabetroute.com, the WMRRC owned three wood-burning steam engines at that time, named the Canary (subsequently renamed Green Spring), Western Maryland, and Patapsco.

Unfortunately, as the “Wild Mary” approached Reisterstown, the railroad ran out of money. Yet, with financial aid offered by Baltimore, the company managed to “forge ahead” to as far as Union Bridge, when another calamity struck in the form of the “Great Rebellion” of 1861-1865.

It was probably somewhat fortuitous for the “Wild Mary” that progress on the railroad had come to a halt at the outset of the insurrection. The already expansive Baltimore and Ohio Railroad suffered tremendously during the course of the four-year uprising, having lost, in the first year alone, dozens of steam engines that were either captured or destroyed, along with hundreds of railroad cars suffering a similar fate, as well as having sustained the loss of nearly two dozen railroad bridges and three dozen miles of railroad.

The WMRRC did, however, play a role during the hostilities in providing what transportation it could for troop movement and supplies.

Also, in 1864, before the end of the rebellion, the railroad had acquired two more wood-burning steam engines, named as being the “Pipe Creek” and the “Monocacy,” according to alphabetroute.com, which further stated that the aforementioned three steam engines, and the additional two, had remained as having been “the only five named locomotives on the Western Maryland.”

Rise and Fall of “Wild Mary”

In the wake of the insurrection, the WMRRC had commenced to move forward with growth and expansion. By 1873, a mere handful of steam engines had grown to 12, and the company was in the process of converting them from wood-burning to coal-burning engines.

In 1874, John Mifflin Hood, a former lieutenant in the Confederate Army (in 1861, he had volunteered to serve in the [Confederate] Second Maryland Regiment, in the Army of Northern Virginia), became president of the WMRRC. (Hood was wounded seven times during the course of the insurrection, but he had become adept in topographical engineering skills while serving in the military.)

Under Hood’s presidency at the helm of the WMRRC, he was credited with, basically, having modernized the railroad, along with its accompanying expansion. He held the presidency position for some 28 years.

Further, under Hood’s guidance, the “Western Maryland trackage grew to 270 miles of steel track, stretching into Pennsylvania and Western Maryland,” according to alphabetroute.com., and the fleet of steam engines grew to 71 in number. He also had all the then-existing wooden railroad bridges replaced with steel railroad bridges.

On December 1, 1909, three years following Hood’s death, the Western Maryland Railway (WMR) was incorporated, resulting in the railroad’s name change. The reorganization—the result of the bankruptcy of the WMRRC—had also resulted in the new railroad company acquiring the assets of the WMRRC.

At the peak of its operation, the WMR spanned some 835 miles in three states: Maryland, Pennsylvania, and West Virginia. The growth of the WMR was attributed to the increase of coal resources and other industrial development in the Allegany Mountains, “swallowing up” a variety of failing short-line railroads; working out deals with other railroads to use portions of their rail lines; and an aggressive campaign to conquer the Alleghenies.

While being primarily a freight line, the WMR did provide some passenger-line services. According to alphabetroute.com, “On the Western Maryland, passenger trains are typically thought of as two to four car trains with an RPO/baggage car and one or two coaches,” although the railroad did dabble in a few major passenger operations.

Regarding the demise of the WMR, a document located in the archives of the Library of Congress (Historic American Engineering Record collection) noted, “While high construction and maintenance costs, coupled with changes in the transportation industry ultimately led to the railroad’s abandonment, the surviving roadbed and structures continue to bear witness to the sophistication of the era’s engineering and construction capabilities, as well as the bold visions of those who underwrote such projects.”

According to gaptrail.org, during the 1950s, “the WMR’s coal business was in decline, and its lumber shipments had evaporated. Automobile transportation reduced nationwide demand for rail-passenger service.” Most major railroads were also suffering, including the Baltimore and Ohio (B&O) and the Chesapeake and Ohio (C&O) railroads.

As a result of the decline of the value of the WMR, the B&O purchased “a significant amount” of WMR stock, which, as the result of legal entanglements, was placed into a “non-voting trust” fund, where ownership resided until 1964, when the B&O, C&O, and WMR were consolidated into one entity, which ultimately became the Chessie System in 1972/1973, which, in turn, along with the Seaboard Coast Railroad, became the CSX in 1980.

For a more extensive history of the WMR, the reader is referred to The Alphabet Route: Western Maryland Railway at alphabetroute.com.

“Wild Mary” Reincarnated

In 1988, a tourist rail line known as the Allegany Central Railroad (ACR) began to offer rail tours, employing steam and diesel power under the guidance of Jack Showalter, according to the Western Maryland Scenic Railroad website.

The ACR operated rail excursions over three different locations over several decades, one of which occurred via employing the old WMR line between Cumberland and Frostburg, beginning in 1988. The Cumberland and Frostburg portions of the ACR continue to be used for rail excursions to this very day, following a name change in 1991 from the ACR to the Western Maryland Scenic Railroad (WMSR).

The WMSR offers a four-and-a-half-hour steam or diesel-pulled excursion from Cumberland, through the Allegheny Mountains, to Frostburg, which includes a 90-minute stop in Frostburg for tourists and shoppers. Other special-event rides are also offered.

For additional information on the WMSR, visit the organization’s website at wmsr.com.

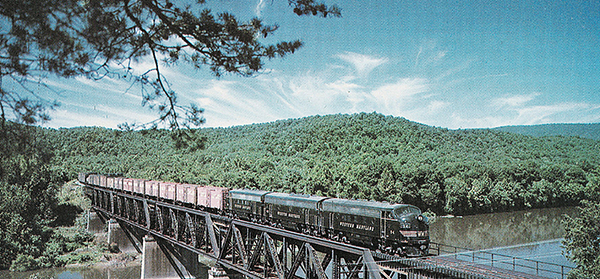

Western Maryland Railroad diesel crossing the Potomac near Little Orleans, Maryland.

Western Maryland Railroad steam engine on the “big curve” at Corriganville, Maryland, 1952.