The B&O Railroad Story

Richard D. L. Fulton

The Baltimore & Ohio Railroad (or more simply referred to as being the B&O) traces its origins back to Baltimore’s economic struggles, which the port city had faced in the mid-to-late 1820s.

Prior to that time, the port city had thrived on engaging in exporting and importing, actually since the founding of its port. Prior to the late 1920s, transporting goods overland into and out of Baltimore had relied heavily on toll roads, turnpikes, Indian paths, and wagon trails.

But then, a new method of transporting goods—the canals and their fleets of canal boats—changed the way that goods were transported across the country to the port cities.

The Erie Canal, completed in 1825, had linked the Great Lake territories with the Hudson River, and more canals were being constructed across Pennsylvania with the goal of delivering goods to the port of Philadelphia.

The construction of the canals cut into Baltimore’s revenues, as their previous share of imported and exported goods was being soaked off by other canal-serviced ports.

The Early Years

The most obvious answer to the solution was to create a canal that would serve the Baltimore port. Thus, as the construction of the Chesapeake and Ohio Canal was initiated in 1828, Baltimore was firmly looking forward to being able to compete with the other port cities.

But to their dismay, it was suddenly realized that the C&O Canal was going to serve Washington, D.C., not Baltimore. The hard luck canal would never be totally complete anyway, but Baltimore was about to discover another means of transporting goods: the “rail road,” as it had initially been termed.

Soon thereafter, an idea was suggested in 1826 by Evan Thomas, brother of Philip E. Thomas (president of the National Mechanics Bank of Baltimore) that rail roads could be constructed and employed to transport goods. Evan Thomas had learned of the possibilities when he had visited England, according to The Great Railroads of North America (Bill Yenne, general editor, and Timothy Jones, editor).

In England, Evan Thomas had witnessed the operations of the British Stockton & Darlington Railroad, a small mining railroad.

Sold on the idea, Philip E. Thomas and George Brown (who was the director of the National Mechanics Bank of Baltimore) then became partners in establishing a “rail road” venture, and on February 28, 1828, incorporated the Baltimore and Ohio Rail Road Company, paving the way for the B&O to become the first (and ultimately the oldest) passenger and freight railroad in the nation.

Yet, the B&O was, at that timeframe, still a long way from the age of steam-driven bullet trains and the age of diesel.

The first leg of tracks was laid between Mount Clare, Baltimore, and Ellicott City, with the first “train” then having been in operation on this short line on May 24, 1930, according to Yenne and Jones. The “trains” consisted of a stagecoach-like car— the first car having been named “The Pioneer”—pulled by horses. The horses also pulled wagons, which were designed for hauling freight.

But horse-drawn railcars were also short-lived, and the Age of Steam was about to commence in earnest.

The Rise of an Empire

On August 24, 1830, the first B&O steam engine made its debut. It was named as being the Tom Thumb, which had been constructed in 1929 by Peter Cooper, according to Yenne and Jones. The Tom Thumb made its first run from Baltimore to Ellicott City, traveling at an average of 18 miles per hour, while hauling a coach with 25 passengers.

The Tom Thumb was subsequently replaced by the York, a more capable engine developed by watchmaker, Phineas David. On December 2, 1831, the B&O had laid rails to Frederick and inaugurated its first run. The York was found to have been capable of hauling as many as five passenger cars and attaining speeds of up to 30 miles per hour.

The York proved to be so successful that the B&O ordered five more from Davis and placed them into service. They included the Atlantic, Thomas Jefferson, James Madison, James Monroe, and J.Q. Adams, according to explorepahistory.com.

On the Fourth of July in 1831, the B&O purchased the first eight-wheeled passenger cars. By 1835, the B&O owned eight steam engines, 44 passenger cars, and 1,078 freight cars, according to Yenne and Jones.

In March 1832, the B&O tracks had been laid to Point of Rocks, and were thereby able to reach Harper’s Ferry on December 1, 1834, where it was temporarily paused, awaiting the construction of the Harper’s Ferry railroad bridge, which was completed in early 1837, according to borail.net/Timeline.html, which also noted that the B&O had reached Martinsburg and Hancock, West Virginia, and Cumberland, all having been in 1842.

On Christmas Eve, 1852, the B&O reached Wheeling, West Virginia, thereby deeming the B&O as being the first railroad to reach the Ohio River from the east coast, and subsequently, the B&O became the first through train from the East Coast to have reached Saint Louis.

The growth of the B&O is much more complex than could be presented here, between buying up other lines or a controlling amount of their stock and entering into agreement with other railroads to use their rail lines. For a more definitive timeline of the evolution of the B&O, refer to borail.net/Timeline.html.

The subsequent War of Rebellion found the B&O serving an unanticipated duty: the transporting of Union troops and supplies to aid the Union forces in their attempts to restore order to the nation.

Serving the Union war effort proved costly to the B&O. By the end of 1861 alone, dozens of B&O steam engines had been destroyed or captured, hundreds of railroad cars had been destroyed or captured, and nearly two dozen B&O railroad bridges had been destroyed, along with more than three-dozen miles of railway.

However, one of the positive outcomes of the war was that, prior to the war, various railroads ran on different tracks’ sizes (referred to as gauges), meaning that one railroad’s engines and cars may or may not have been able to operate on the rails of one another. Lessons learned during the war resulted in a national movement after the war to standardize all the railroads to a common size.

The Last Years

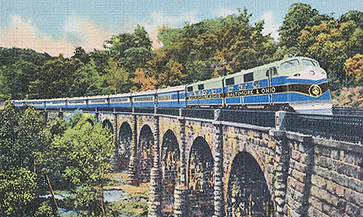

The B&O reached its ultimate peak in the 1950s, when it operated on some 5,658 miles of track between Baltimore, New York City, Chicago, and Saint Louis, the railroad’s tracks spanning a total of 13 states.

But the railroad came upon hard times going into the 1960s, mainly due to financial woes.

This resulted in the Chesapeake and Ohio Railroad (C&O) gaining control of the B&O in 1962, although they continued to operate as separate entities. In 1963, the C&O became officially affiliated with the B&O, thereby integrating the use of the B&O’s personnel, buildings, and railroad equipment with the C&O’s own.

In 1973, the C&O, B&O, and Western Maryland Railroad had been merged into the Chessie System. In 1980, the Chessie System had been merged with the Seaboard Coast Railroad and consolidated into the CSX Corporation. In 1987, the B&O as an entity was dissolved.

For additional information, visit the B&O Railroad Museum in Baltimore, or log onto their website at borail,com. Also recommended is the book, The Great Railroads of North America, by Bill Yenne, Barnes & Noble, 1992.

Additionally, there are numerous videos regarding the B&O railroad, as well as the B&O Railroad Museum, that have been posted on Youtube.com.