Strange Beasts of the Mason-Dixon Line

Richard D. L. Fulton

For hundreds of millions of years, the parade of life that existed beneath the oceans that covered the Mason-Dixon Line to the mountain ranges that rose from beneath them, often seemed like something out of an Edgard Rice Burroughs’ novel with a little Dr. Seuss thrown in from time to time.

From sea life that resembled an octopus in an ice cream cone, to creatures that could be mistaken for a bird, would it not have been for the fact that they also possessed claws and a mouth full of sharp teeth, to a sea creature that could easily take down a large fishing vessel, to animals that looked like they just walked out of a Dr. Seuss zoo, to one whose mysterious existence is still in question, the few examples would be just a few among the many.

Grab a cup of coffee or hot chocolate and have a seat, for you are about to enter the Mason-Dixon ‘Twilight Zone.”

The Orthocones

From some 500 million years ago to around 320 million years ago, much of the land that now comprises Maryland and Pennsylvania lies beneath shallow, tropical to semi-tropical seas, but for the first 100 million years of that time span, the apex predators were the orthocones.

The orthocones (also called nautiloids) were members of a group of animals called cephalopods and were the direct ancestors of the present-day Chambered Nautilus, squids, and octopi.

Orthocone refers to their straight cone-like shell, which served as home to an octopus-like animal, whose head protruded from the widened, opened end of the cone. They had large complex eyes (some of the most highly developed for the animals of that time), and had from ten to dozens of tentacles surrounding their peaked mouths.

While fossils of the orthocones can be found in Maryland and Pennsylvania, the shallow seas seemed to have held their average sizes to between a few inches to more than 12 inches. Elsewhere, in deeper water fossil deposits, their shells have been discovered up to 15 feet in length.

The orthocones’ dominance demised as fish began to evolve, along with gigantic sea scorpions, competing for orthocone food sources, and possibly even feeding on orthocones.

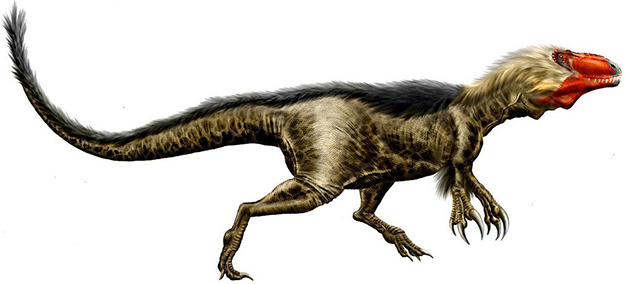

Dryptosaurus

If one found oneself strolling along the shores of an ancient river that flowed through Prince George’s County some 115 million years ago, and ran across a gaggle of brightly-feathered chicks poking around and anything that appeared edible along the shore, one might reconsider the temptation of tossing the chicks some bread crumbs to eat, especially if mother Dryptosaurus is nearby, hidden in the tree line, seeking more-substantive food for her chicks.

The chicks would not have been some strange little flightless birds of any sort. They would have been the young of one the feathered dinosaurs who also happened to be savage apex predators, and an early member of a dinosaur group that would eventually produce the even more infamous Tyrannosaurus rex.

Although Dryptosaurus, whose fossil remains have been found in Prince George’s County was flightless, the dinosaur is also related to groups of dinosaurs that were not only feathered, but possessed wings, numerous examples of which were discovered in fossil sites with the People’s Republic of China. In fact, one of the dinosaurs found there had four wings.

It is generally believed the early-winged dinosaurs were primarily gliders, climbing trees and launching into the air as per the flying squirrels, but it appears their descendants developed muscles that allowed them to flap the wings, thus making them the Wright brothers of the reptile world.

Aepycamelus

Most Marylanders have been long acquainted with the Calvert Cliffs exposed along the Western Shore of the Chesapeake Bay. The cliffs contain countless millions of fossils of marine life that existed during the Miocene Epoch some 23 to 5 million years ago,

However, every now and then, collectors have run across the teeth and bones of animals that did not live in the sea, but instead thrived along the shore and plains of ancient Maryland. These fossils are believed to have been those of animals who died in or around rivers, which in turn washed the remains into the nearby sea (Maryland bordered an ocean. The bay did not exist then).

Found among those remains are those which belonged to Maryland’s native camel, Aepycamelus. The name Aepycamelus is Greek and means “high and steep camel,” so-named in reference that Aepycamelus was a long-necked camel, as opposed to those which exist today.

The Maryland camel was about 16 feet in length and 10 feet in height and was comparable to a giraffe—and likely acting and feeding in a similar fashion. The camel’s long neck allowed the animal to browse on trees at a height not readily accessible to its competing plant eaters.

There is no way to ascertain how common, or uncommon, the long-necked camels were among the wildlife of Maryland due to the scarcity of remains found, which are themselves a rarity.

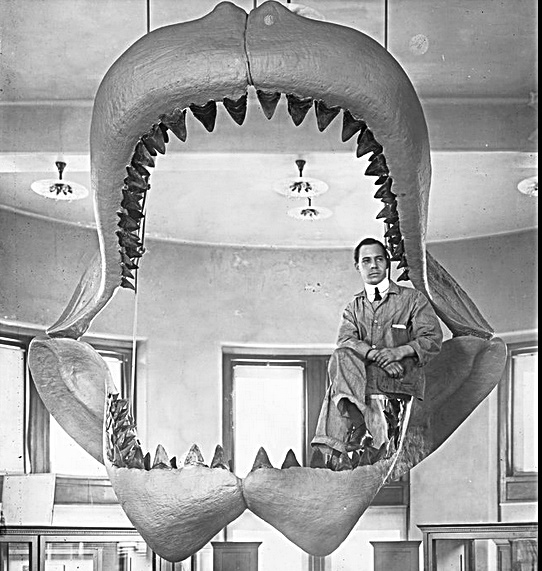

Otodus

While Aepycamelus peacefully foraged on the plains and in the woodlands of prehistoric Maryland, Maryland’s most deadly predators were busy prowling the waters along the Maryland shore.

This beast was Otodus megalodon, formerly known as Carcharodon megalodon—a giant 60-foot shark that rendered the Maryland waters dangerous for any other creatures sharing those waters, even including the whales.

The beast was previously classified as a “great white shark,” but recently it was “demoted” to having been a giant mackerel shark, a change of status that in no way impacted the ferocity of the beast, whose razor-sharp, triangular teeth, each of which could reach up to six inches in height.

Otodus reportedly evolved from the great white sharks some 115 million years ago, around the time when Dryptosaurus was feeding their chicks in Prince George’s County. Otodus megalodon was the largest predatory shark that ever lived, and a full-grown, 60-foot Otodus could weigh in at 65 tons.

Fortunately for Maryland fishermen and women, Otodus megalodon became extinct around 2.5 million years ago. The cause of the animal’s extinction was probably due to the diminishing population of baleen whales (no doubt one of the giant sharks’ favorite meals), and the increase in the numbers of smaller, competing predatory sharks, such as the actual “great white” sharks.

The Beast of South Mountain

The mystery of the South Mountain beast, that reportedly roamed the rolling foothills of Appalachia in Adams County appears to have never been entirely resolved.

One of the initial sightings of this strange animal was reported in the January 20, 1921, edition of The Gettysburg Times, which stated that the creature was seen sitting on a rock, and that, “When the monstrous animal saw that it was discovered by some Mount Rock citizens, it arose, stretched itself, and disappeared into a nearby wood.”

In the initial reports and those that followed, the creature was described as everything from a gorilla to a kangaroo. Although it was theorized that the mysterious animal must have escaped from the crash of a circus train in the general area, no record of any such crash was ever located. Some suggested it was just a bear, but many who had sighted the beast were hunters who would have certainly known a bear upon seeing one.

The first “organized” hunt for the mysterious animal occurred in the wake of the January 20 sighting, when “50 men gathered on Pike Hill near Idaville and again tried to kill the elusive creature,” The Times reported, adding that “the animal escaped across the snow to Daniels’ Hill near the Adams-Cumberland line.”

Sightings continued into the summer, with chase after chase, and sighting after sighting, having produced no definitive identification of the beast, until encounters just seemed to drop off in August.

Whether or not the creature had moved on would never be resolved, but sightings picked up again from the 1980s into the 2000s in the Michaux State Forest area.

For more information on the South Mountain creature, see “The Strange Beast of South Mountain” in the March and April 2023 issues of The Catoctin Banner.

Dryptosaurus

(Josep Asensi, durbed.deviantart.com via Wikimedia)

Aepycamelus

(Nobu Tamura, spinops.blogspot.com via Wikimedia)

Otodus

(American Museum of Natural History)