Maryland’s “Atlantis”

Richard D. L. Fulton

Once upon a time…Maryland was some 300 miles wider than the width of the state as it presently exists. So, where did 300 miles of Maryland go?

The land that is no longer there teemed with life—plants and animals, and quite likely, humans as well. But some major events changed all of that over time and, ultimately, reduced the width of what would someday be Maryland, from some 550 miles in width to 250 miles.

Maryland’s Land that Time Forgot attained its peak of existence some 20,000 years ago during the last great Ice Age (also known as the Pleistocene Epoch), when so much of the earth’s water was tied up in continental ice sheets (glaciers) that sea levels dropped, exposing vast miles of land that had once been underwater, resulting in the shoreline in Maryland having been extended by 300 miles out to (what was then) sea.

Geological records have established that the Earth has experienced at least 17 periods of ice ages (by-products of global cooling), each followed by periods of interglacial global warming.

The Landscape of “Atlantis”

In what eventually became the Mid-Atlantic states, one mile thick, continental ice sheets had formed as far south as mid-Pennsylvania, but Maryland was spared from the development of glaciers, although the presence of the ice sheets to the north did generate rather cold, average temperatures in Maryland, but not so cold as to render the environment uninhabitable.

The Appalachian Mountains were there, but they were much reduced throughout the millions of years of erosion. However, east of the mountains to the sea, prehistoric Maryland was dominated by tundra, marshlands, and forests of conifers, such as spruce, fir, and pine trees, according to Maryland.gov.

It was during this period that the Susquehanna River had carved its way across the tundra, ultimately setting the stage for the creation of the Chesapeake Bay, as it had begun to fill an impact crater created by a meteor that had struck Maryland in the area of the Delmarva Peninsula, some 35 million years before the last ice age.

The Wildlife of “Atlantis”

So, what kind of wildlife inhabited the 300 now-missing miles of Maryland during, and in the wake of, the ice age? Prior to 1912, the only evidence of the former inhabitants of Maryland’s “Atlantis” had consisted of random finds that had been washed upon the beaches of the bay, consisting of isolated bones and teeth that clearly did not belong to the 20-million-year-old Miocene Epoch marine fossils of the Calvert Cliffs.

So how did they get there?

During the 1960s, the author of this article discovered a U-shaped cut of gray clay in an isolated section of the Calvert Cliffs that contained the remains of freshwater fish and fossil pinecones.

Hence, this provided evidence that remains of Pleistocene animals and plants that had been found along the bay beaches among the Miocene fossils had been deposited by the streams and rivers that had been generated by the glacial meltwaters and that had cut into the Miocene deposits of the bay.

But the real “motherload” of evidence occurred in 1912, when a cave was discovered in the Cumberland area that contained a treasure trove of the remains of the animals that had inhabited Maryland’s “Atlantis.”

In addition to the isolated finds along the beaches of the Chesapeake, the Cumberland Cave yielded the remains of more than 25 species of ice age and post-ice age animals.

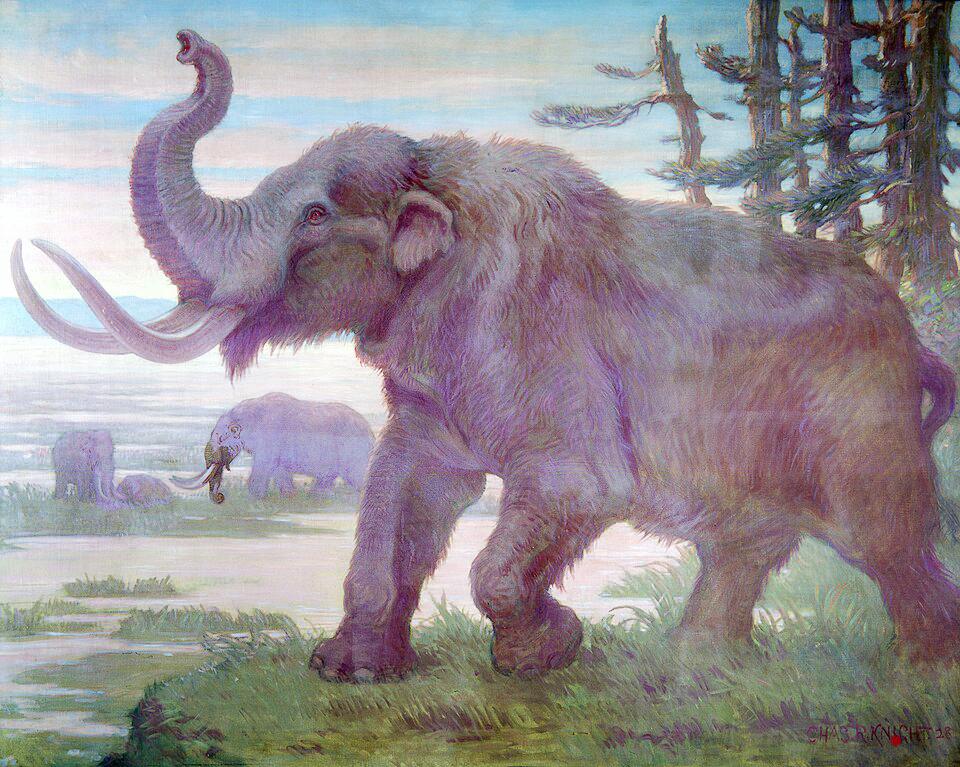

The largest of those creatures included the Woolly Mammoth, the fully haired elephant species that could weigh up to eight tons; mastodons; and the deadly, ambush predator, the saber-tooth tiger, whose saber-like canines could reach (depending on the species) up to a foot in length.

In addition to the above, some of the other larger animals included elk and the grizzly bear. Another find of interest included the coyote, meaning that, contrary to popular beliefs, the coyote in Maryland today is not an invasive animal, but rather, is a member of an indigenous one!

The remains of other wildlife that had inhabited the ever-changing climate of Maryland’s ice age and post-ice age included mustelids species (a group that includes weasels, badgers, otters, etc.) that are only found in the Arctic today, according to hive.blog/Cumberland Cavern.com.

More familiar animals that inhabited Maryland’s “Atlantis” included prehistoric bats, owls, long-tailed shrews, fish, minks, red squirrels, muskrats, porcupine, jumping mice, pika, rabbits, peccaries (wild pigs), tapirs, deer, bison, and beavers.

The People of “Atlantis”

The humans that had inhabited the lost world of Maryland’s “Atlantis” are little known, since they would have likely lived along the then-existing coastal lands (as well as in the more interior areas of the state), where all manner of food sources had existed, from crabs to shellfish and from fish to game.

There is little doubt that they were there because they had also left traces of their inhabitation in fields and woods that remain today that lie above the present sea level.

The first inhabitants were nomadic, living in extended family units (thousands of years before tribes even existed), following game trails as wildlife migrated back and forth, depending on the seasons. Settlements, as a concept, did not exist, but seasonal encampments did exist.

The nomadic peoples are generally classified by the stone objects—such as spearheads—they left behind. For many decades, it was believed that the oldest nomadic inhabitants that had seasonally lived in Maryland were a hunting and gathering culture known as the Clovis people, who encamped throughout much of Maryland’s piedmont and coastal plain areas.

These people, who it is believed came into the Americas from Asia via a North Pacific land bridge exposed by the drop in the sea levels, no doubt encamped and hunted on the 300 miles of lost land from 12,800 to 13,400 years ago. Thus, it was held that they were the first humans to arrive in the Americas. But, now, all that has changed. The Clovis may not have actually been the first people.

Recent archaeological discoveries have revealed artifacts even older than the Clovis and left by an older nomadic group of people dating back to more than 22,000 years.

The question of where these people came from is still being studied, but it was noted that some of their artifacts resemble those of prehistoric Europeans.

Some authorities even further suggested, “Some early Americans came not from Asia, it seems, but by way of Europe,” according to Smithsonian Magazine (“The Very First Americans May Have Had European Roots,” Colin Schultz, October 25, 2013).

Others maintain they were paleo-Asian and paleo-European hybrids that came to North America across the same land bridge that was subsequently used by the Clovis people.

According to Nature’s website, in an article entitled “Coming to America,” by Andrew Curry, “For decades, scientists thought that the Clovis hunters were the first to cross the Arctic to America. They were wrong—and now they need a better theory.”

Whatever the answer may be, archaeological discoveries that have been recovered verified that this unknown culture existed in Maryland more than 20,000 years ago and that they certainly hunted and encamped in Maryland’s 300 missing miles.

The Fate of “Atlantis”

For thousands of years following the end of the ice age, continued melting of the great continental ice sheets had caused the ocean levels to rise, thereby eating away at the Maryland shoreline.

Over the millenniums, Maryland’s now-missing 300 miles had eroded away and slipped beneath the sea, along with the evidence of its former vegetative grandeur, and the wildlife and humans that had occupied it.

Like the Atlantis of legend, Maryland’s “Atlantis” now resides beneath the sea… at least until the next ice age.

American Mastodon Source: Mural at the Field Museum, wikimedia.com

Saber Tooth Tiger: Source: American Museum of Natural History, wikimedia.com