Maryland on Stamps & Covers

Richard D. L. Fulton

Frederick Douglass

“A man’s rights rest in three boxes. The ballot box, the jury box, and the cartridge box.” ~Frederick Douglass

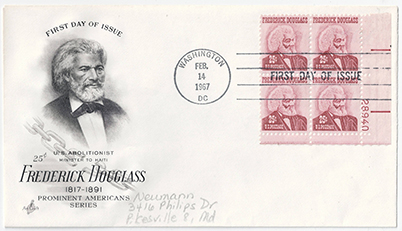

The United States Postal Service (USPS) issued a 25-cent stamp on February 14, 1967, and a 32-cent stamp on June 29, 1995, commemorating Frederick Augustus Washington Bailey, better known as Frederick Douglass.

The 1967 stamp was issued as one of several stamps commemorating Prominent Americans and was issued on the date of Douglass’s “claimed” birthday and depicted the bust of Douglass. The First Day of Issue covers (FDCs) were postmarked in Washington, D.C., although Douglass was actually born in Maryland.

The 1995 stamp was issued as part of a set of stamps commemorating the 130th anniversary of the American Civil War, depicting Douglass delivering a speech, and the FDCs were postmarked in Gettysburg, Pennsylvania.

The Early Years

Frederick Douglass was born into slavery on a plantation in Talbot County, Maryland. His actual birthdate remains unknown, Douglass having stated, “I have no accurate knowledge of my age, never having seen any authentic record containing it,” according to Narrative of the Life of Frederick Douglass, an American Slave, written by Douglass and published in 1845.

He later estimated he was born in 1817 (although records of Douglass’ former owner, Aaron Anthony, suggest his birth year was in February 1818, according to historian Dickson J. Preston), yet he didn’t know the day. He chose the date of February 14 because of his mother, Harriet Bailey, who called him her “little Valentine,” and who, at his birth, named him Frederick Augustus Washington Bailey (Douglass assumed the name Frederick Douglass after his escape). Douglass never knew who his father was, but believed he was white.

Douglass wrote that slave children were removed from their mothers “at a very early age,” but that, after separation, his mother would visit him at night and then slip away by morning, writing, “I do not recollect of ever seeing my mother by the light of day. She was with me in the night. She would lie down with me, and get me to sleep, but long before I waked she was gone.”

Douglass subsequently lived with his maternal grandmother and slave, Betsy Bailey, and his grandfather, a freed slave named Isaac Bailey, until he was six years old.

Douglass’ “Great Escape”

Douglass was handed down to a number of owners and overseers—one or two kindly, and others nothing short of brutal.

At the age of six, he was separated from his grandparents and fell under the auspices of Wye House plantation overseer, Aaron Anthony, in Talbot County.

Upon Anthony’s death in 1826, Douglass was given to the Auld family. In 1833, he was sent to work on a farm owned by Edward Covey, a poor farmer, where he was subject to frequent whippings.

In 1835, Douglass was hired out to William Gardiner and employed in Gardiner’s shipyard in Fells Point, where he was further abused by the white employees, according to Frederick Douglass’ 1855 “My Bondage and My Freedom (nationalhumanitiescenter.org).”

Douglass successfully escaped bondage on September 3, 1838, by “boarding a northbound train of the Philadelphia, Wilmington and Baltimore Railroad in Baltimore,” according to Today in African-American Transportation History – 1818: Frederick Douglass Begins His Journey Into History (transportationhistory.org).

Life After Freedom

Douglass became a leading advocate for not only emancipation, but for “women’s rights, temperance, peace, land reform, free public education, and the abolition of capital punishment,” according to Roy Finkenbine’s Frederick Douglass, published in American National Biography (anb.org).

Douglass married Anna Murray, a free slave, around 1838, with whom he also fathered five children: Lewis, Frederick Jr., Charles, Rosetta, and Annie.

After Anna’s death, he married Helen Pitts, Douglass’s white former secretary.

For additional information, the reader can read Douglass’ Narrative of the Life of Frederick Douglass, an American Slave online at the Library of Congress website.