Making Mountain Dew, White Lightning, Hooch, Moonshine

James Rada, Jr.

When the sale, production, and transportation of alcohol was banned in the United States in 1919, citizens had to choose between becoming teetotalers or criminals. Many law-abiding citizens chose the latter.

Since a person could get in trouble buying a drink, people who did it, didn’t talk about it. That didn’t mean that it wasn’t happening. Underground bars, or speakeasies, weren’t advertised. People knew about them by word of mouth. You got in by knowing someone or knowing a password. Manufacturing moved to stills hidden in the woods or basements.

Moonshining (the illegal manufacture or distribution of alcohol) has been around since the Whiskey Rebellion in the 1790s. The Western Pennsylvanians, who refused to pay the federal taxes on homemade liquor, were the country’s first moonshiners.

However, it wasn’t until the Prohibition era that moonshining took off since the demand for liquor increased. With the profits increasing—a quart of moonshine could fetch $16 in Hagerstown ($225 in today’s dollars)—more and more people were willing to risk being arrested and became moonshiners, rumrunners, and bootleggers.

How to Make Moonshine

Kenny Bray was a Western Maryland coal miner in the early 20th century. I have a copy of his unpublished memoir. It includes a section on moonshining and how it is made.

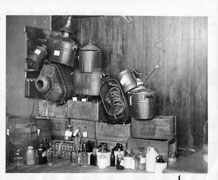

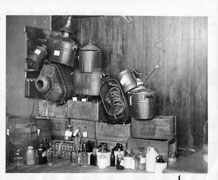

First, you need a still, a tub, and a source of running water.

The average still during the early decades of the 20th century was a 14.5-gallon copper wash boiler. A worm, which was a long piece of 3/8 inch or 1/2 inch copper tubing, ran from the top of the boiler to the cooling tub. The boiler lid was sealed with flour paste. The worm was coiled inside the cooling tub, with the end coming out near the bottom. A small stream of water ran into the tub to cool the coils.

Once the still is set up, here is the recipe: a bushel of corn or grain; 50 pounds of sugar; a couple cakes of yeast; and 35-50 gallons of water.

It is all mixed in a barrel and left to ferment into corn mash. The barrel is covered but it is not sealed like the boiler. As it ferments, the mash becomes milky white. It is occasionally mixed. After the mash has fermented, the grain will settle to the bottom, and the mixture is said to be “worked off” and is ready for distilling.

When the sale, production, and transportation of alcohol was banned in the United States in 1919, citizens had to choose between becoming teetotalers or criminals. Many law-abiding citizens chose the latter.

Since a person could get in trouble buying a drink, people who did it, didn’t talk about it. That didn’t mean that it wasn’t happening. Underground bars, or speakeasies, weren’t advertised. People knew about them by word of mouth. You got in by knowing someone or knowing a password. Manufacturing moved to stills hidden in the woods or basements.

Moonshining (the illegal manufacture or distribution of alcohol) has been around since the Whiskey Rebellion in the 1790s. The Western Pennsylvanians, who refused to pay the federal taxes on homemade liquor, were the country’s first moonshiners.

However, it wasn’t until the Prohibition era that moonshining took off since the demand for liquor increased. With the profits increasing—a quart of moonshine could fetch $16 in Hagerstown ($225 in today’s dollars)—more and more people were willing to risk being arrested and became moonshiners, rumrunners, and bootleggers.

How to Make Moonshine

Kenny Bray was a Western Maryland coal miner in the early 20th century. I have a copy of his unpublished memoir. It includes a section on moonshining and how it is made.

First, you need a still, a tub, and a source of running water.

The average still during the early decades of the 20th century was a 14.5-gallon copper wash boiler. A worm, which was a long piece of 3/8 inch or 1/2 inch copper tubing, ran from the top of the boiler to the cooling tub. The boiler lid was sealed with flour paste. The worm was coiled inside the cooling tub, with the end coming out near the bottom. A small stream of water ran into the tub to cool the coils.

Once the still is set up, here is the recipe: a bushel of corn or grain; 50 pounds of sugar; a couple cakes of yeast; and 35-50 gallons of water.

It is all mixed in a barrel and left to ferment into corn mash. The barrel is covered but it is not sealed like the boiler. As it ferments, the mash becomes milky white. It is occasionally mixed. After the mash has fermented, the grain will settle to the bottom, and the mixture is said to be “worked off” and is ready for distilling.

In preparation for the distilling, the copper parts of the still are cleaned with vinegar and salt to remove any rust.

The boiler is filled with mash to within a few inches of the top and set over a low fire. Since alcohol has a lower boiling point than water, the alcohol evaporates while the water does not. The alcohol vapor travels up into the worm and moves through the tubing. As it moves through the water-cooled tub, the vapor condenses back into liquid alcohol. What comes out at the end of the worm is moonshine.

This first run is called a “singling.” It is not pleasant to drink and will leave a burning sensation in your mouth and throat.

After the singling run, the still is emptied and cleaned. Then the singling is poured into the boiler, along with water, and the cooking process is done again. This is called “doubling,” and Bray calls it the best grade of moonshine. After this doubling run, you would probably have about 10 gallons of moonshine.

In preparation for the distilling, the copper parts of the still are cleaned with vinegar and salt to remove any rust.

The boiler is filled with mash to within a few inches of the top and set over a low fire. Since alcohol has a lower boiling point than water, the alcohol evaporates while the water does not. The alcohol vapor travels up into the worm and moves through the tubing. As it moves through the water-cooled tub, the vapor condenses back into liquid alcohol. What comes out at the end of the worm is moonshine.

This first run is called a “singling.” It is not pleasant to drink and will leave a burning sensation in your mouth and throat.

After the singling run, the still is emptied and cleaned. Then the singling is poured into the boiler, along with water, and the cooking process is done again. This is called “doubling,” and Bray calls it the best grade of moonshine. After this doubling run, you would probably have about 10 gallons of moonshine.

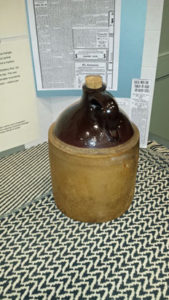

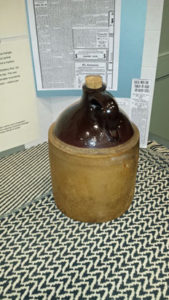

However, if you ever see old pictures of moonshine jugs with X’s on them, that represents the number of times run through; XXX isn’t porn, it’s high-grade moonshine.

The original mash can be used up to three times by adding more sugar, yeast, and water.

This was all done without meters and gauges to tell alcohol was no longer coming out of the worm. The way that moonshiners could tell a run was done was that they would catch a teaspoon of moonshine out of the worm and throw it on the fire. If it flashed, they kept cooking. If it sizzled, they stopped.

Bray’s grandfather used honey instead of sugar and corn to make a good, smooth whiskey called, Honey Brandy.

However, former Catoctin Mountain Park Ranger Debra Mills pointed out during a presentation at the Thurmont Regional Library, “No still ever makes whiskey, because it doesn’t have time to age.”

Moonshining produces distilled alcohol.

Some moonshiners weren’t too concerned with their quality of product and took shortcuts in making moonshine. Some of the things that Prohibition moonshiners did include:

• Doubling the first run in mash instead of water.

• Using a 55 gal. steel drum instead of a copper boiler.

• Letting the still run too long.

• Put rubbing alcohol in the mash when it was ready to run, which would increase the amount of the run 2 to 1 in direct proportion to the amount of alcohol put in, one pint of 70 percent rubbing alcohol would make two pints of 70 proof moonshine.

• Putting other materials in the mash to ferment, such as overripe fruit.

• Coloring moonshine with tobacco juice or iodine instead of vanilla to make it taste strong when it wasn’t.

• Using a 14 oz. bottle and selling it for the same price as a 16 oz. bottle.

Wayne Martin, a Thurmont resident whose grandfathers were moonshiners, said his Grandfather Henry used to speed up the “aging” process by putting the kegs on hot water pipes, which supposedly also made the moonshine taste better.

The Waynesboro Record Herald reported about a moonshiner who took the ultimate shortcut. He sold three Waynesboro men three pints of moonshine for $2 a pint. It was a good deal that the men jumped at. “Naturally, after they had it in their possession, they wanted to sample the liquor, and on doing so found that they had purchased muddy mountain water with no more ‘kick’ than the water which runs into the pipes in homes of Waynesboro from the town reservoir,” the newspaper reported.

Thurmont Moonshining

Mills points out that Catoctin Mountain was much more barren during the Prohibition era, and the people who lived on it were poor.

“Prohibition was probably a good thing economically for people in this area,” Mills said.

Having stills operating also gave farmers a place to sell their crops. Although corn was the most popular grain for moonshine, Elmer Black said in a 2015 interview that he only ever knew of rye being raised to be sold to the local moonshiners in the area.

The finished product was often shipped out of the area on the railroad in barrels labeled cornmeal, according to Mills.

It could leave other ways as well. Black recalled that his grandfather would often run moonshine right under the nose of the county sheriff and his deputies. He would get the family together to take a ride in their Studebaker, and off they would go. There was an ulterior motive for the drive, though. Moonshine was hidden underneath the seats.

“My grandfather would wave ‘hi’ as they went by the sheriff,” Black said.

Two of Black’s uncles were some of the biggest bootleggers around the Thurmont area. Even his father was known to drive moonshine out of the area to sell. One time he took Black and his siblings along for the ride. The kids fell asleep.

“The three of us woke up and asked, ‘who lives here?’” Black said. “Some senator, they told us. They were rolling the barrels up to the house.”

Stills were hidden on Catoctin Mountain near streams that could supply them with the water needed for the moonshine recipes. According to Black, if you follow the streams on Catoctin Mountain upriver, you can still see the remnants of stills that were destroyed.

Martin shared some of his family stories during a presentation at the Thurmont Regional Library about moonshining.

One grandfather kept a quarter keg of moonshine in his attic, and when friends would come by with Mason jars, Martin’s grandfather would tell his son to “go up and get some ‘shine for the friends.”

At some point, Martin’s grandfather moved the keg from the attic to the basement and buried it in the coal pile.

Once, revenue agents came by wanting to search the house while Martin’s father was alone. The boy didn’t know what to do because he couldn’t get on the phone to call his parents, so he let the revenue agents in to search the house.

They started in the attic, which worried Martin’s father, but the men didn’t find anything. Martin’s father thought he was safe and that the moonshine was no longer in the house. The revenue agents continued their search, ending up in the basement.

One of the agents saw the coal pile and wondered if moonshine might be buried in it. Martin’s father, not knowing that was the case, held up the coal shovel and told the agents, “Go ahead and dig, but you’ve got to put it all back or my dad will be mad.”

Luckily, the agents were lazy and chose not to dig. Martin’s grandfather moved the moonshine out of the house after that.

The revenuers did eventually catch up with Martin’s grandfather. According to Martin, they came in the front door of the house, chasing Martin’s grandfather while the man went out the back door. The revenuers chased after him.

Martin’s father, a young boy at the time, chased after the revenuers. “Dad, he caught up with one revenuer and bit him on the leg and my grandfather got away,” Martin said.

The Blue Blazes Still

However, if you ever see old pictures of moonshine jugs with X’s on them, that represents the number of times run through; XXX isn’t porn, it’s high-grade moonshine.

The original mash can be used up to three times by adding more sugar, yeast, and water.

This was all done without meters and gauges to tell alcohol was no longer coming out of the worm. The way that moonshiners could tell a run was done was that they would catch a teaspoon of moonshine out of the worm and throw it on the fire. If it flashed, they kept cooking. If it sizzled, they stopped.

Bray’s grandfather used honey instead of sugar and corn to make a good, smooth whiskey called, Honey Brandy.

However, former Catoctin Mountain Park Ranger Debra Mills pointed out during a presentation at the Thurmont Regional Library, “No still ever makes whiskey, because it doesn’t have time to age.”

Moonshining produces distilled alcohol.

Some moonshiners weren’t too concerned with their quality of product and took shortcuts in making moonshine. Some of the things that Prohibition moonshiners did include:

• Doubling the first run in mash instead of water.

• Using a 55 gal. steel drum instead of a copper boiler.

• Letting the still run too long.

• Put rubbing alcohol in the mash when it was ready to run, which would increase the amount of the run 2 to 1 in direct proportion to the amount of alcohol put in, one pint of 70 percent rubbing alcohol would make two pints of 70 proof moonshine.

• Putting other materials in the mash to ferment, such as overripe fruit.

• Coloring moonshine with tobacco juice or iodine instead of vanilla to make it taste strong when it wasn’t.

• Using a 14 oz. bottle and selling it for the same price as a 16 oz. bottle.

Wayne Martin, a Thurmont resident whose grandfathers were moonshiners, said his Grandfather Henry used to speed up the “aging” process by putting the kegs on hot water pipes, which supposedly also made the moonshine taste better.

The Waynesboro Record Herald reported about a moonshiner who took the ultimate shortcut. He sold three Waynesboro men three pints of moonshine for $2 a pint. It was a good deal that the men jumped at. “Naturally, after they had it in their possession, they wanted to sample the liquor, and on doing so found that they had purchased muddy mountain water with no more ‘kick’ than the water which runs into the pipes in homes of Waynesboro from the town reservoir,” the newspaper reported.

Thurmont Moonshining

Mills points out that Catoctin Mountain was much more barren during the Prohibition era, and the people who lived on it were poor.

“Prohibition was probably a good thing economically for people in this area,” Mills said.

Having stills operating also gave farmers a place to sell their crops. Although corn was the most popular grain for moonshine, Elmer Black said in a 2015 interview that he only ever knew of rye being raised to be sold to the local moonshiners in the area.

The finished product was often shipped out of the area on the railroad in barrels labeled cornmeal, according to Mills.

It could leave other ways as well. Black recalled that his grandfather would often run moonshine right under the nose of the county sheriff and his deputies. He would get the family together to take a ride in their Studebaker, and off they would go. There was an ulterior motive for the drive, though. Moonshine was hidden underneath the seats.

“My grandfather would wave ‘hi’ as they went by the sheriff,” Black said.

Two of Black’s uncles were some of the biggest bootleggers around the Thurmont area. Even his father was known to drive moonshine out of the area to sell. One time he took Black and his siblings along for the ride. The kids fell asleep.

“The three of us woke up and asked, ‘who lives here?’” Black said. “Some senator, they told us. They were rolling the barrels up to the house.”

Stills were hidden on Catoctin Mountain near streams that could supply them with the water needed for the moonshine recipes. According to Black, if you follow the streams on Catoctin Mountain upriver, you can still see the remnants of stills that were destroyed.

Martin shared some of his family stories during a presentation at the Thurmont Regional Library about moonshining.

One grandfather kept a quarter keg of moonshine in his attic, and when friends would come by with Mason jars, Martin’s grandfather would tell his son to “go up and get some ‘shine for the friends.”

At some point, Martin’s grandfather moved the keg from the attic to the basement and buried it in the coal pile.

Once, revenue agents came by wanting to search the house while Martin’s father was alone. The boy didn’t know what to do because he couldn’t get on the phone to call his parents, so he let the revenue agents in to search the house.

They started in the attic, which worried Martin’s father, but the men didn’t find anything. Martin’s father thought he was safe and that the moonshine was no longer in the house. The revenue agents continued their search, ending up in the basement.

One of the agents saw the coal pile and wondered if moonshine might be buried in it. Martin’s father, not knowing that was the case, held up the coal shovel and told the agents, “Go ahead and dig, but you’ve got to put it all back or my dad will be mad.”

Luckily, the agents were lazy and chose not to dig. Martin’s grandfather moved the moonshine out of the house after that.

The revenuers did eventually catch up with Martin’s grandfather. According to Martin, they came in the front door of the house, chasing Martin’s grandfather while the man went out the back door. The revenuers chased after him.

Martin’s father, a young boy at the time, chased after the revenuers. “Dad, he caught up with one revenuer and bit him on the leg and my grandfather got away,” Martin said.

The Blue Blazes Still

On July 31, 1929, two cars drove up Catoctin Mountain on Route 77. Six men rode in the cars. Only five would be alive two hours later.

The cars pulled off the side of the road. Frederick County Deputy John Hemp and Lester Hoffman climbed out of one of them.

Although not a deputy, Hoffman was the only one in the group who knew his way through the forest to what an informant had described a week earlier as a “large liquor plant.”

“The officers, in attempting to creep up on the small vale in which the still was situated, ascended a winding mountain path, which led abruptly to the scene of the tragedy,” reported the Frederick Post.

As they neared the still, shots rang out. Deputy Clyde Hauver fell and the deputies scattered for cover, as the moonshiners fired on them, hidden by the underbrush.

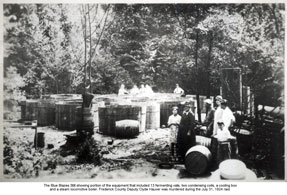

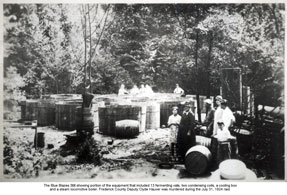

Once Hauver was on his way to Frederick, the remaining deputies used picks and axes to destroy the vats and boiler. The newspaper reported that Blue Blazes Still was one of the largest and best equipped in Frederick County, according to reports. It had a boiler from a steam locomotive, twenty 500-gallon-capacity wooden vats, filled with corn mash, two condensing coils, and a cooling box.

A National Park Service (NPS) ranger told me that the still produced alcohol so fast that if a man took away a five-gallon bucket of alcohol and dumped it into a vat, by the time he returned to the still, another bucket would be filled and waiting to be removed.

A manhunt started for the moonshiners and eight men were eventually jailed. Charles Lewis was convicted of first-degree murder in the Washington County Circuit Court on March 7, 1930. Governor Theodore McKeldin commuted the sentence in 1950, when Lewis was sixty-five. He died a short time after his release.

There is still much speculation over whether Lewis was the actual murderer. Mills pointed out that he was probably the informant who told the sheriff’s department about the operation. Names get suggested as do motives, such as a love triangle gone bad or one man coveting another man’s job, but no other person has been conclusively shown to be the killer.

Today, the Blue Blazes Still is gone, but the NPS has a 50-gallon pot still captured in a Tennessee raid on the same location. NPS uses it for presentations about moonshining in the mountains.

The NPS actually operated the still for demonstrations from 1970 to 1989. It was the first still ever to operate legally on government property, according to Thurmont Historian George Wireman.

When the NPS started operating the still, the Hagerstown Morning Herald reported, “National Park officials hasten to assure that the whiskey is not for presidential consumption, although the pungent odor of mash undoubtedly wafts over the mountain retreat to be inhaled occasionally by VIP nostrils.”

However, though the park had received permission from the Treasury Department to manufacture whiskey, park personnel hadn’t talked to state authorities about it. The Hagerstown Morning Herald wrote, “on the first day the still was in operation, an agent of the state’s alcohol tax division appeared at the park with two deputies, all set to make another raid on Blue Blazes.” Since the still was on federal property, they couldn’t do anything about it, though.

“I’m still known as the only park superintendent in the service who’s been raided for being a moonshiner,” former Park Superintendent Frank Mentzer told the newspaper.

Moonshining in Pen Mar

Pen Mar, with its ideal location as a resort on the border between Maryland and Pennsylvania, became a popular spot for bootleggers to hide their stills. Also, being at Pen Mar put them close to people who wanted to relax and enjoy themselves with a drink.

In 1921, an informant told police that there were thirteen stills that he knew of in the vicinity of Pen Mar. The bootleggers were making good money selling their product, though they didn’t stay very long in one place.

The Gettysburg Compiler reported that one informant about the bootlegging at Pen Mar saw “a bootlegger with a suitcase, placed the latter on a rock near the old Blue Mountain House path and did a land office business by handing the liquor out by the pint and half pint to people who appeared from among the bushes.”

After a few minutes, he closed up shop and disappeared into the woods, only to reappear in another location about half an hour or so later.

In 1925, revenuers tried to get Daniel Toms’ 30-gallon still in Cascade. He held them off for a short time with a shot gun, but they eventually surrounded him and caught him and his henchmen.

Smithsburg Moonshining War

Revenuers also spent plenty of time in Smithsburg, combing the hills for moonshiners. They tried to pass themselves off as tourist hikers.

Smithsburg made national headlines as having an “old-time mountain feud” between John Cline and Henry Russman. There were reports of night raiding, indiscriminate shooting, and fights. They were accused of wrecking a church, dynamiting a sawmill, killing one person, and wounding others. A 1923 article estimated that there were 500 stills between Hagerstown and the Pennsylvania line. The interest in this fighting may have been due in part to the recent coal mine riots that had grown so violent across the country.

One newspaper reported about the moonshiners, “They are unmolested. It would be as much as an officer’s life would be worth to try and interfere. The natives are silent. They know a bullet in the dark would follow any giving of information.”

End of an Era

Due to its unpopularity, Prohibition soon ended after the election of Franklin D. Roosevelt in 1932. With that, prices of liquor dropped and moonshining lost its appeal to many people.

On July 31, 1929, two cars drove up Catoctin Mountain on Route 77. Six men rode in the cars. Only five would be alive two hours later.

The cars pulled off the side of the road. Frederick County Deputy John Hemp and Lester Hoffman climbed out of one of them.

Although not a deputy, Hoffman was the only one in the group who knew his way through the forest to what an informant had described a week earlier as a “large liquor plant.”

“The officers, in attempting to creep up on the small vale in which the still was situated, ascended a winding mountain path, which led abruptly to the scene of the tragedy,” reported the Frederick Post.

As they neared the still, shots rang out. Deputy Clyde Hauver fell and the deputies scattered for cover, as the moonshiners fired on them, hidden by the underbrush.

Once Hauver was on his way to Frederick, the remaining deputies used picks and axes to destroy the vats and boiler. The newspaper reported that Blue Blazes Still was one of the largest and best equipped in Frederick County, according to reports. It had a boiler from a steam locomotive, twenty 500-gallon-capacity wooden vats, filled with corn mash, two condensing coils, and a cooling box.

A National Park Service (NPS) ranger told me that the still produced alcohol so fast that if a man took away a five-gallon bucket of alcohol and dumped it into a vat, by the time he returned to the still, another bucket would be filled and waiting to be removed.

A manhunt started for the moonshiners and eight men were eventually jailed. Charles Lewis was convicted of first-degree murder in the Washington County Circuit Court on March 7, 1930. Governor Theodore McKeldin commuted the sentence in 1950, when Lewis was sixty-five. He died a short time after his release.

There is still much speculation over whether Lewis was the actual murderer. Mills pointed out that he was probably the informant who told the sheriff’s department about the operation. Names get suggested as do motives, such as a love triangle gone bad or one man coveting another man’s job, but no other person has been conclusively shown to be the killer.

Today, the Blue Blazes Still is gone, but the NPS has a 50-gallon pot still captured in a Tennessee raid on the same location. NPS uses it for presentations about moonshining in the mountains.

The NPS actually operated the still for demonstrations from 1970 to 1989. It was the first still ever to operate legally on government property, according to Thurmont Historian George Wireman.

When the NPS started operating the still, the Hagerstown Morning Herald reported, “National Park officials hasten to assure that the whiskey is not for presidential consumption, although the pungent odor of mash undoubtedly wafts over the mountain retreat to be inhaled occasionally by VIP nostrils.”

However, though the park had received permission from the Treasury Department to manufacture whiskey, park personnel hadn’t talked to state authorities about it. The Hagerstown Morning Herald wrote, “on the first day the still was in operation, an agent of the state’s alcohol tax division appeared at the park with two deputies, all set to make another raid on Blue Blazes.” Since the still was on federal property, they couldn’t do anything about it, though.

“I’m still known as the only park superintendent in the service who’s been raided for being a moonshiner,” former Park Superintendent Frank Mentzer told the newspaper.

Moonshining in Pen Mar

Pen Mar, with its ideal location as a resort on the border between Maryland and Pennsylvania, became a popular spot for bootleggers to hide their stills. Also, being at Pen Mar put them close to people who wanted to relax and enjoy themselves with a drink.

In 1921, an informant told police that there were thirteen stills that he knew of in the vicinity of Pen Mar. The bootleggers were making good money selling their product, though they didn’t stay very long in one place.

The Gettysburg Compiler reported that one informant about the bootlegging at Pen Mar saw “a bootlegger with a suitcase, placed the latter on a rock near the old Blue Mountain House path and did a land office business by handing the liquor out by the pint and half pint to people who appeared from among the bushes.”

After a few minutes, he closed up shop and disappeared into the woods, only to reappear in another location about half an hour or so later.

In 1925, revenuers tried to get Daniel Toms’ 30-gallon still in Cascade. He held them off for a short time with a shot gun, but they eventually surrounded him and caught him and his henchmen.

Smithsburg Moonshining War

Revenuers also spent plenty of time in Smithsburg, combing the hills for moonshiners. They tried to pass themselves off as tourist hikers.

Smithsburg made national headlines as having an “old-time mountain feud” between John Cline and Henry Russman. There were reports of night raiding, indiscriminate shooting, and fights. They were accused of wrecking a church, dynamiting a sawmill, killing one person, and wounding others. A 1923 article estimated that there were 500 stills between Hagerstown and the Pennsylvania line. The interest in this fighting may have been due in part to the recent coal mine riots that had grown so violent across the country.

One newspaper reported about the moonshiners, “They are unmolested. It would be as much as an officer’s life would be worth to try and interfere. The natives are silent. They know a bullet in the dark would follow any giving of information.”

End of an Era

Due to its unpopularity, Prohibition soon ended after the election of Franklin D. Roosevelt in 1932. With that, prices of liquor dropped and moonshining lost its appeal to many people.

When the sale, production, and transportation of alcohol was banned in the United States in 1919, citizens had to choose between becoming teetotalers or criminals. Many law-abiding citizens chose the latter.

Since a person could get in trouble buying a drink, people who did it, didn’t talk about it. That didn’t mean that it wasn’t happening. Underground bars, or speakeasies, weren’t advertised. People knew about them by word of mouth. You got in by knowing someone or knowing a password. Manufacturing moved to stills hidden in the woods or basements.

Moonshining (the illegal manufacture or distribution of alcohol) has been around since the Whiskey Rebellion in the 1790s. The Western Pennsylvanians, who refused to pay the federal taxes on homemade liquor, were the country’s first moonshiners.

However, it wasn’t until the Prohibition era that moonshining took off since the demand for liquor increased. With the profits increasing—a quart of moonshine could fetch $16 in Hagerstown ($225 in today’s dollars)—more and more people were willing to risk being arrested and became moonshiners, rumrunners, and bootleggers.

How to Make Moonshine

Kenny Bray was a Western Maryland coal miner in the early 20th century. I have a copy of his unpublished memoir. It includes a section on moonshining and how it is made.

First, you need a still, a tub, and a source of running water.

The average still during the early decades of the 20th century was a 14.5-gallon copper wash boiler. A worm, which was a long piece of 3/8 inch or 1/2 inch copper tubing, ran from the top of the boiler to the cooling tub. The boiler lid was sealed with flour paste. The worm was coiled inside the cooling tub, with the end coming out near the bottom. A small stream of water ran into the tub to cool the coils.

Once the still is set up, here is the recipe: a bushel of corn or grain; 50 pounds of sugar; a couple cakes of yeast; and 35-50 gallons of water.

It is all mixed in a barrel and left to ferment into corn mash. The barrel is covered but it is not sealed like the boiler. As it ferments, the mash becomes milky white. It is occasionally mixed. After the mash has fermented, the grain will settle to the bottom, and the mixture is said to be “worked off” and is ready for distilling.

When the sale, production, and transportation of alcohol was banned in the United States in 1919, citizens had to choose between becoming teetotalers or criminals. Many law-abiding citizens chose the latter.

Since a person could get in trouble buying a drink, people who did it, didn’t talk about it. That didn’t mean that it wasn’t happening. Underground bars, or speakeasies, weren’t advertised. People knew about them by word of mouth. You got in by knowing someone or knowing a password. Manufacturing moved to stills hidden in the woods or basements.

Moonshining (the illegal manufacture or distribution of alcohol) has been around since the Whiskey Rebellion in the 1790s. The Western Pennsylvanians, who refused to pay the federal taxes on homemade liquor, were the country’s first moonshiners.

However, it wasn’t until the Prohibition era that moonshining took off since the demand for liquor increased. With the profits increasing—a quart of moonshine could fetch $16 in Hagerstown ($225 in today’s dollars)—more and more people were willing to risk being arrested and became moonshiners, rumrunners, and bootleggers.

How to Make Moonshine

Kenny Bray was a Western Maryland coal miner in the early 20th century. I have a copy of his unpublished memoir. It includes a section on moonshining and how it is made.

First, you need a still, a tub, and a source of running water.

The average still during the early decades of the 20th century was a 14.5-gallon copper wash boiler. A worm, which was a long piece of 3/8 inch or 1/2 inch copper tubing, ran from the top of the boiler to the cooling tub. The boiler lid was sealed with flour paste. The worm was coiled inside the cooling tub, with the end coming out near the bottom. A small stream of water ran into the tub to cool the coils.

Once the still is set up, here is the recipe: a bushel of corn or grain; 50 pounds of sugar; a couple cakes of yeast; and 35-50 gallons of water.

It is all mixed in a barrel and left to ferment into corn mash. The barrel is covered but it is not sealed like the boiler. As it ferments, the mash becomes milky white. It is occasionally mixed. After the mash has fermented, the grain will settle to the bottom, and the mixture is said to be “worked off” and is ready for distilling.

In preparation for the distilling, the copper parts of the still are cleaned with vinegar and salt to remove any rust.

The boiler is filled with mash to within a few inches of the top and set over a low fire. Since alcohol has a lower boiling point than water, the alcohol evaporates while the water does not. The alcohol vapor travels up into the worm and moves through the tubing. As it moves through the water-cooled tub, the vapor condenses back into liquid alcohol. What comes out at the end of the worm is moonshine.

This first run is called a “singling.” It is not pleasant to drink and will leave a burning sensation in your mouth and throat.

After the singling run, the still is emptied and cleaned. Then the singling is poured into the boiler, along with water, and the cooking process is done again. This is called “doubling,” and Bray calls it the best grade of moonshine. After this doubling run, you would probably have about 10 gallons of moonshine.

In preparation for the distilling, the copper parts of the still are cleaned with vinegar and salt to remove any rust.

The boiler is filled with mash to within a few inches of the top and set over a low fire. Since alcohol has a lower boiling point than water, the alcohol evaporates while the water does not. The alcohol vapor travels up into the worm and moves through the tubing. As it moves through the water-cooled tub, the vapor condenses back into liquid alcohol. What comes out at the end of the worm is moonshine.

This first run is called a “singling.” It is not pleasant to drink and will leave a burning sensation in your mouth and throat.

After the singling run, the still is emptied and cleaned. Then the singling is poured into the boiler, along with water, and the cooking process is done again. This is called “doubling,” and Bray calls it the best grade of moonshine. After this doubling run, you would probably have about 10 gallons of moonshine.

However, if you ever see old pictures of moonshine jugs with X’s on them, that represents the number of times run through; XXX isn’t porn, it’s high-grade moonshine.

The original mash can be used up to three times by adding more sugar, yeast, and water.

This was all done without meters and gauges to tell alcohol was no longer coming out of the worm. The way that moonshiners could tell a run was done was that they would catch a teaspoon of moonshine out of the worm and throw it on the fire. If it flashed, they kept cooking. If it sizzled, they stopped.

Bray’s grandfather used honey instead of sugar and corn to make a good, smooth whiskey called, Honey Brandy.

However, former Catoctin Mountain Park Ranger Debra Mills pointed out during a presentation at the Thurmont Regional Library, “No still ever makes whiskey, because it doesn’t have time to age.”

Moonshining produces distilled alcohol.

Some moonshiners weren’t too concerned with their quality of product and took shortcuts in making moonshine. Some of the things that Prohibition moonshiners did include:

• Doubling the first run in mash instead of water.

• Using a 55 gal. steel drum instead of a copper boiler.

• Letting the still run too long.

• Put rubbing alcohol in the mash when it was ready to run, which would increase the amount of the run 2 to 1 in direct proportion to the amount of alcohol put in, one pint of 70 percent rubbing alcohol would make two pints of 70 proof moonshine.

• Putting other materials in the mash to ferment, such as overripe fruit.

• Coloring moonshine with tobacco juice or iodine instead of vanilla to make it taste strong when it wasn’t.

• Using a 14 oz. bottle and selling it for the same price as a 16 oz. bottle.

Wayne Martin, a Thurmont resident whose grandfathers were moonshiners, said his Grandfather Henry used to speed up the “aging” process by putting the kegs on hot water pipes, which supposedly also made the moonshine taste better.

The Waynesboro Record Herald reported about a moonshiner who took the ultimate shortcut. He sold three Waynesboro men three pints of moonshine for $2 a pint. It was a good deal that the men jumped at. “Naturally, after they had it in their possession, they wanted to sample the liquor, and on doing so found that they had purchased muddy mountain water with no more ‘kick’ than the water which runs into the pipes in homes of Waynesboro from the town reservoir,” the newspaper reported.

Thurmont Moonshining

Mills points out that Catoctin Mountain was much more barren during the Prohibition era, and the people who lived on it were poor.

“Prohibition was probably a good thing economically for people in this area,” Mills said.

Having stills operating also gave farmers a place to sell their crops. Although corn was the most popular grain for moonshine, Elmer Black said in a 2015 interview that he only ever knew of rye being raised to be sold to the local moonshiners in the area.

The finished product was often shipped out of the area on the railroad in barrels labeled cornmeal, according to Mills.

It could leave other ways as well. Black recalled that his grandfather would often run moonshine right under the nose of the county sheriff and his deputies. He would get the family together to take a ride in their Studebaker, and off they would go. There was an ulterior motive for the drive, though. Moonshine was hidden underneath the seats.

“My grandfather would wave ‘hi’ as they went by the sheriff,” Black said.

Two of Black’s uncles were some of the biggest bootleggers around the Thurmont area. Even his father was known to drive moonshine out of the area to sell. One time he took Black and his siblings along for the ride. The kids fell asleep.

“The three of us woke up and asked, ‘who lives here?’” Black said. “Some senator, they told us. They were rolling the barrels up to the house.”

Stills were hidden on Catoctin Mountain near streams that could supply them with the water needed for the moonshine recipes. According to Black, if you follow the streams on Catoctin Mountain upriver, you can still see the remnants of stills that were destroyed.

Martin shared some of his family stories during a presentation at the Thurmont Regional Library about moonshining.

One grandfather kept a quarter keg of moonshine in his attic, and when friends would come by with Mason jars, Martin’s grandfather would tell his son to “go up and get some ‘shine for the friends.”

At some point, Martin’s grandfather moved the keg from the attic to the basement and buried it in the coal pile.

Once, revenue agents came by wanting to search the house while Martin’s father was alone. The boy didn’t know what to do because he couldn’t get on the phone to call his parents, so he let the revenue agents in to search the house.

They started in the attic, which worried Martin’s father, but the men didn’t find anything. Martin’s father thought he was safe and that the moonshine was no longer in the house. The revenue agents continued their search, ending up in the basement.

One of the agents saw the coal pile and wondered if moonshine might be buried in it. Martin’s father, not knowing that was the case, held up the coal shovel and told the agents, “Go ahead and dig, but you’ve got to put it all back or my dad will be mad.”

Luckily, the agents were lazy and chose not to dig. Martin’s grandfather moved the moonshine out of the house after that.

The revenuers did eventually catch up with Martin’s grandfather. According to Martin, they came in the front door of the house, chasing Martin’s grandfather while the man went out the back door. The revenuers chased after him.

Martin’s father, a young boy at the time, chased after the revenuers. “Dad, he caught up with one revenuer and bit him on the leg and my grandfather got away,” Martin said.

The Blue Blazes Still

However, if you ever see old pictures of moonshine jugs with X’s on them, that represents the number of times run through; XXX isn’t porn, it’s high-grade moonshine.

The original mash can be used up to three times by adding more sugar, yeast, and water.

This was all done without meters and gauges to tell alcohol was no longer coming out of the worm. The way that moonshiners could tell a run was done was that they would catch a teaspoon of moonshine out of the worm and throw it on the fire. If it flashed, they kept cooking. If it sizzled, they stopped.

Bray’s grandfather used honey instead of sugar and corn to make a good, smooth whiskey called, Honey Brandy.

However, former Catoctin Mountain Park Ranger Debra Mills pointed out during a presentation at the Thurmont Regional Library, “No still ever makes whiskey, because it doesn’t have time to age.”

Moonshining produces distilled alcohol.

Some moonshiners weren’t too concerned with their quality of product and took shortcuts in making moonshine. Some of the things that Prohibition moonshiners did include:

• Doubling the first run in mash instead of water.

• Using a 55 gal. steel drum instead of a copper boiler.

• Letting the still run too long.

• Put rubbing alcohol in the mash when it was ready to run, which would increase the amount of the run 2 to 1 in direct proportion to the amount of alcohol put in, one pint of 70 percent rubbing alcohol would make two pints of 70 proof moonshine.

• Putting other materials in the mash to ferment, such as overripe fruit.

• Coloring moonshine with tobacco juice or iodine instead of vanilla to make it taste strong when it wasn’t.

• Using a 14 oz. bottle and selling it for the same price as a 16 oz. bottle.

Wayne Martin, a Thurmont resident whose grandfathers were moonshiners, said his Grandfather Henry used to speed up the “aging” process by putting the kegs on hot water pipes, which supposedly also made the moonshine taste better.

The Waynesboro Record Herald reported about a moonshiner who took the ultimate shortcut. He sold three Waynesboro men three pints of moonshine for $2 a pint. It was a good deal that the men jumped at. “Naturally, after they had it in their possession, they wanted to sample the liquor, and on doing so found that they had purchased muddy mountain water with no more ‘kick’ than the water which runs into the pipes in homes of Waynesboro from the town reservoir,” the newspaper reported.

Thurmont Moonshining

Mills points out that Catoctin Mountain was much more barren during the Prohibition era, and the people who lived on it were poor.

“Prohibition was probably a good thing economically for people in this area,” Mills said.

Having stills operating also gave farmers a place to sell their crops. Although corn was the most popular grain for moonshine, Elmer Black said in a 2015 interview that he only ever knew of rye being raised to be sold to the local moonshiners in the area.

The finished product was often shipped out of the area on the railroad in barrels labeled cornmeal, according to Mills.

It could leave other ways as well. Black recalled that his grandfather would often run moonshine right under the nose of the county sheriff and his deputies. He would get the family together to take a ride in their Studebaker, and off they would go. There was an ulterior motive for the drive, though. Moonshine was hidden underneath the seats.

“My grandfather would wave ‘hi’ as they went by the sheriff,” Black said.

Two of Black’s uncles were some of the biggest bootleggers around the Thurmont area. Even his father was known to drive moonshine out of the area to sell. One time he took Black and his siblings along for the ride. The kids fell asleep.

“The three of us woke up and asked, ‘who lives here?’” Black said. “Some senator, they told us. They were rolling the barrels up to the house.”

Stills were hidden on Catoctin Mountain near streams that could supply them with the water needed for the moonshine recipes. According to Black, if you follow the streams on Catoctin Mountain upriver, you can still see the remnants of stills that were destroyed.

Martin shared some of his family stories during a presentation at the Thurmont Regional Library about moonshining.

One grandfather kept a quarter keg of moonshine in his attic, and when friends would come by with Mason jars, Martin’s grandfather would tell his son to “go up and get some ‘shine for the friends.”

At some point, Martin’s grandfather moved the keg from the attic to the basement and buried it in the coal pile.

Once, revenue agents came by wanting to search the house while Martin’s father was alone. The boy didn’t know what to do because he couldn’t get on the phone to call his parents, so he let the revenue agents in to search the house.

They started in the attic, which worried Martin’s father, but the men didn’t find anything. Martin’s father thought he was safe and that the moonshine was no longer in the house. The revenue agents continued their search, ending up in the basement.

One of the agents saw the coal pile and wondered if moonshine might be buried in it. Martin’s father, not knowing that was the case, held up the coal shovel and told the agents, “Go ahead and dig, but you’ve got to put it all back or my dad will be mad.”

Luckily, the agents were lazy and chose not to dig. Martin’s grandfather moved the moonshine out of the house after that.

The revenuers did eventually catch up with Martin’s grandfather. According to Martin, they came in the front door of the house, chasing Martin’s grandfather while the man went out the back door. The revenuers chased after him.

Martin’s father, a young boy at the time, chased after the revenuers. “Dad, he caught up with one revenuer and bit him on the leg and my grandfather got away,” Martin said.

The Blue Blazes Still

On July 31, 1929, two cars drove up Catoctin Mountain on Route 77. Six men rode in the cars. Only five would be alive two hours later.

The cars pulled off the side of the road. Frederick County Deputy John Hemp and Lester Hoffman climbed out of one of them.

Although not a deputy, Hoffman was the only one in the group who knew his way through the forest to what an informant had described a week earlier as a “large liquor plant.”

“The officers, in attempting to creep up on the small vale in which the still was situated, ascended a winding mountain path, which led abruptly to the scene of the tragedy,” reported the Frederick Post.

As they neared the still, shots rang out. Deputy Clyde Hauver fell and the deputies scattered for cover, as the moonshiners fired on them, hidden by the underbrush.

Once Hauver was on his way to Frederick, the remaining deputies used picks and axes to destroy the vats and boiler. The newspaper reported that Blue Blazes Still was one of the largest and best equipped in Frederick County, according to reports. It had a boiler from a steam locomotive, twenty 500-gallon-capacity wooden vats, filled with corn mash, two condensing coils, and a cooling box.

A National Park Service (NPS) ranger told me that the still produced alcohol so fast that if a man took away a five-gallon bucket of alcohol and dumped it into a vat, by the time he returned to the still, another bucket would be filled and waiting to be removed.

A manhunt started for the moonshiners and eight men were eventually jailed. Charles Lewis was convicted of first-degree murder in the Washington County Circuit Court on March 7, 1930. Governor Theodore McKeldin commuted the sentence in 1950, when Lewis was sixty-five. He died a short time after his release.

There is still much speculation over whether Lewis was the actual murderer. Mills pointed out that he was probably the informant who told the sheriff’s department about the operation. Names get suggested as do motives, such as a love triangle gone bad or one man coveting another man’s job, but no other person has been conclusively shown to be the killer.

Today, the Blue Blazes Still is gone, but the NPS has a 50-gallon pot still captured in a Tennessee raid on the same location. NPS uses it for presentations about moonshining in the mountains.

The NPS actually operated the still for demonstrations from 1970 to 1989. It was the first still ever to operate legally on government property, according to Thurmont Historian George Wireman.

When the NPS started operating the still, the Hagerstown Morning Herald reported, “National Park officials hasten to assure that the whiskey is not for presidential consumption, although the pungent odor of mash undoubtedly wafts over the mountain retreat to be inhaled occasionally by VIP nostrils.”

However, though the park had received permission from the Treasury Department to manufacture whiskey, park personnel hadn’t talked to state authorities about it. The Hagerstown Morning Herald wrote, “on the first day the still was in operation, an agent of the state’s alcohol tax division appeared at the park with two deputies, all set to make another raid on Blue Blazes.” Since the still was on federal property, they couldn’t do anything about it, though.

“I’m still known as the only park superintendent in the service who’s been raided for being a moonshiner,” former Park Superintendent Frank Mentzer told the newspaper.

Moonshining in Pen Mar

Pen Mar, with its ideal location as a resort on the border between Maryland and Pennsylvania, became a popular spot for bootleggers to hide their stills. Also, being at Pen Mar put them close to people who wanted to relax and enjoy themselves with a drink.

In 1921, an informant told police that there were thirteen stills that he knew of in the vicinity of Pen Mar. The bootleggers were making good money selling their product, though they didn’t stay very long in one place.

The Gettysburg Compiler reported that one informant about the bootlegging at Pen Mar saw “a bootlegger with a suitcase, placed the latter on a rock near the old Blue Mountain House path and did a land office business by handing the liquor out by the pint and half pint to people who appeared from among the bushes.”

After a few minutes, he closed up shop and disappeared into the woods, only to reappear in another location about half an hour or so later.

In 1925, revenuers tried to get Daniel Toms’ 30-gallon still in Cascade. He held them off for a short time with a shot gun, but they eventually surrounded him and caught him and his henchmen.

Smithsburg Moonshining War

Revenuers also spent plenty of time in Smithsburg, combing the hills for moonshiners. They tried to pass themselves off as tourist hikers.

Smithsburg made national headlines as having an “old-time mountain feud” between John Cline and Henry Russman. There were reports of night raiding, indiscriminate shooting, and fights. They were accused of wrecking a church, dynamiting a sawmill, killing one person, and wounding others. A 1923 article estimated that there were 500 stills between Hagerstown and the Pennsylvania line. The interest in this fighting may have been due in part to the recent coal mine riots that had grown so violent across the country.

One newspaper reported about the moonshiners, “They are unmolested. It would be as much as an officer’s life would be worth to try and interfere. The natives are silent. They know a bullet in the dark would follow any giving of information.”

End of an Era

Due to its unpopularity, Prohibition soon ended after the election of Franklin D. Roosevelt in 1932. With that, prices of liquor dropped and moonshining lost its appeal to many people.

On July 31, 1929, two cars drove up Catoctin Mountain on Route 77. Six men rode in the cars. Only five would be alive two hours later.

The cars pulled off the side of the road. Frederick County Deputy John Hemp and Lester Hoffman climbed out of one of them.

Although not a deputy, Hoffman was the only one in the group who knew his way through the forest to what an informant had described a week earlier as a “large liquor plant.”

“The officers, in attempting to creep up on the small vale in which the still was situated, ascended a winding mountain path, which led abruptly to the scene of the tragedy,” reported the Frederick Post.

As they neared the still, shots rang out. Deputy Clyde Hauver fell and the deputies scattered for cover, as the moonshiners fired on them, hidden by the underbrush.

Once Hauver was on his way to Frederick, the remaining deputies used picks and axes to destroy the vats and boiler. The newspaper reported that Blue Blazes Still was one of the largest and best equipped in Frederick County, according to reports. It had a boiler from a steam locomotive, twenty 500-gallon-capacity wooden vats, filled with corn mash, two condensing coils, and a cooling box.

A National Park Service (NPS) ranger told me that the still produced alcohol so fast that if a man took away a five-gallon bucket of alcohol and dumped it into a vat, by the time he returned to the still, another bucket would be filled and waiting to be removed.

A manhunt started for the moonshiners and eight men were eventually jailed. Charles Lewis was convicted of first-degree murder in the Washington County Circuit Court on March 7, 1930. Governor Theodore McKeldin commuted the sentence in 1950, when Lewis was sixty-five. He died a short time after his release.

There is still much speculation over whether Lewis was the actual murderer. Mills pointed out that he was probably the informant who told the sheriff’s department about the operation. Names get suggested as do motives, such as a love triangle gone bad or one man coveting another man’s job, but no other person has been conclusively shown to be the killer.

Today, the Blue Blazes Still is gone, but the NPS has a 50-gallon pot still captured in a Tennessee raid on the same location. NPS uses it for presentations about moonshining in the mountains.

The NPS actually operated the still for demonstrations from 1970 to 1989. It was the first still ever to operate legally on government property, according to Thurmont Historian George Wireman.

When the NPS started operating the still, the Hagerstown Morning Herald reported, “National Park officials hasten to assure that the whiskey is not for presidential consumption, although the pungent odor of mash undoubtedly wafts over the mountain retreat to be inhaled occasionally by VIP nostrils.”

However, though the park had received permission from the Treasury Department to manufacture whiskey, park personnel hadn’t talked to state authorities about it. The Hagerstown Morning Herald wrote, “on the first day the still was in operation, an agent of the state’s alcohol tax division appeared at the park with two deputies, all set to make another raid on Blue Blazes.” Since the still was on federal property, they couldn’t do anything about it, though.

“I’m still known as the only park superintendent in the service who’s been raided for being a moonshiner,” former Park Superintendent Frank Mentzer told the newspaper.

Moonshining in Pen Mar

Pen Mar, with its ideal location as a resort on the border between Maryland and Pennsylvania, became a popular spot for bootleggers to hide their stills. Also, being at Pen Mar put them close to people who wanted to relax and enjoy themselves with a drink.

In 1921, an informant told police that there were thirteen stills that he knew of in the vicinity of Pen Mar. The bootleggers were making good money selling their product, though they didn’t stay very long in one place.

The Gettysburg Compiler reported that one informant about the bootlegging at Pen Mar saw “a bootlegger with a suitcase, placed the latter on a rock near the old Blue Mountain House path and did a land office business by handing the liquor out by the pint and half pint to people who appeared from among the bushes.”

After a few minutes, he closed up shop and disappeared into the woods, only to reappear in another location about half an hour or so later.

In 1925, revenuers tried to get Daniel Toms’ 30-gallon still in Cascade. He held them off for a short time with a shot gun, but they eventually surrounded him and caught him and his henchmen.

Smithsburg Moonshining War

Revenuers also spent plenty of time in Smithsburg, combing the hills for moonshiners. They tried to pass themselves off as tourist hikers.

Smithsburg made national headlines as having an “old-time mountain feud” between John Cline and Henry Russman. There were reports of night raiding, indiscriminate shooting, and fights. They were accused of wrecking a church, dynamiting a sawmill, killing one person, and wounding others. A 1923 article estimated that there were 500 stills between Hagerstown and the Pennsylvania line. The interest in this fighting may have been due in part to the recent coal mine riots that had grown so violent across the country.

One newspaper reported about the moonshiners, “They are unmolested. It would be as much as an officer’s life would be worth to try and interfere. The natives are silent. They know a bullet in the dark would follow any giving of information.”

End of an Era

Due to its unpopularity, Prohibition soon ended after the election of Franklin D. Roosevelt in 1932. With that, prices of liquor dropped and moonshining lost its appeal to many people.