Look Up

by Mitchell Tester, College Student

It’s cold out tonight. I open the slide door, and the frigid air hits me as I walk out my back door, telescope in hand. I make my way over to the table and set down the piece of equipment. I adjust it up to what appears as a bright star in the sky. As I look, I realize it’s one of the brightest. To my knowledge, though, I know this is no star, but our largest planet, Jupiter. I turn on the red dot finder and aim it at this beacon of light. Both eyes open, I dial it in. Taking off the eye piece cover of my telescope, I look in and I see it. The cloud bands of Jupiter, the orange and red hue, the white bands stretching across the entirety of the planet. A planet with no known life, a planet of gas.

In a sense, due to Jupiter being composed entirely of gas, you may think you could just pass right through it, but that is impossible. Despite it being made full of gas, Jupiter gets so dense that it practically has a solid core of liquid and gas. Not solid in the traditional sense, though, it being so tightly wound in the middle that it would appear as solid but is still a gaseous form. I readjust my eyes, positioning myself more comfortably against the telescope.

I look again. I think to how small our neighboring planet, Mars, looks through my telescope, an orange pea in the sky. It appears like I am looking at a star and not a planet, due to it looking so far away. Mars being a “meager” 62 million miles away, while Jupiter is a staggering 408 million miles away, yet it still looks large in my telescope compared to the pea-size Mars. What I realize is how big Jupiter must be for me to see it this large in my 20 mm eyepiece and measly 4-inch reflector telescope—so far away that it would take us 600 days to get to it. Jupiter is so big, in fact, that 1,300 Earths could fit inside of it. Jupiter is our biggest planet, large enough to fit every planet in our solar system inside of it, with some additional room to spare.

I adjust my telescope once more, noticing again the white bands on Jupiter’s nonexistent “surface,” or the troposphere, as the visible layer is officially called. The white cloud bands are made of ammonia and water, so cold that it plummets to temperatures of -230 degrees Fahrenheit. These bands are home to winds so strong that they are four times stronger than the worst hurricane on our home, Earth. So strong that the winds reach 300-plus miles per hour. The white bands are cool-sinking gas in Jupiter’s layers, while the dark bands on Jupiter are hot-rising gas. Jupiter, appearing as a star in the night sky, speaks to something, that something being the fact that, in a sense, Jupiter is a failed star. Made up of mostly hydrogen and helium, it may remind you of something else in our Solar System. The center of it all, the Sun. The Sun, in addition to Jupiter, is made up of mostly hydrogen and helium. Jupiter would be like the Sun, meaning that it can fuse hydrogen into helium, if only it were even larger than it already is. So, despite Jupiter being made up of the same elements, it is simply not large enough. Who knows, if Jupiter were large enough to be a star, we would have a binary star system, which is actually the most common form of solar system. Our one-star system is unique in a sense.

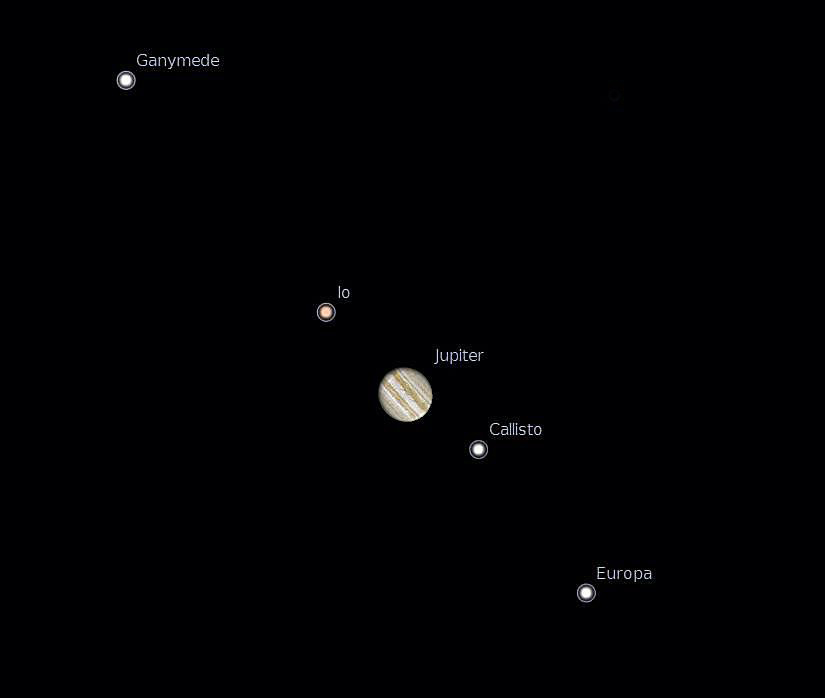

I come back to the telescope, this time adjusting the eye piece once more. I see three dots to the left of Jupiter, and one more to the right. These distant specks of light are not stars, but some of Jupiter’s moons. Its largest moons are Ganymede, Io, Callisto, and Europa. These moons are called Galilean moons due to their discoverer, Galileo Galilei. Galileo discovered these moons through a 24-inch-long, 1.5-inch-wide telescope, all the way back in 1610. Galileo was so ahead of his time that these four moons were considered Jupiter’s only natural satellites until 1892, when Jupiter’s fifth largest moon was discovered, named Amalthea.

I see the moons as beacons of light, with the rightmost moon being Ganymede, Jupiter’s largest moon. Ganymede is roughly half rock and half water ice by mass. It is gray in color, resembling our Moon—not in composition exactly, but in appearance. Next to Ganymede is Jupiter’s third largest moon, named Io—Io being the name of a Greek mythological figure, a follower of Zeus. Io is a fiery hellscape to put it simply, the most volcanically active moon in our solar system. It is yellow in appearance, like the color of sulfur. This checks out, as it has a composition of mostly silicate rock, sulfur, sulfur dioxide, molten iron, and iron sulfide. The largest volcano on Io is Loki Patera. It is 126 miles in diameter (the largest on Earth is 400, found on the Pacific Ocean floor, east of Japan). Additionally, Io contains a lava lake.

Now that I have taken into account the two moons to the left of Jupiter, I adjust my eyes to the right of it. Next to Jupiter on the right is its second largest moon, Callisto. Callisto is one of my favorites. As many of the pictures of Callisto show, it appears that there are spots of light on the surface. It is a cool sight to see, and I suggest you look it up for yourself. Callisto is made up of water ice, and rock. The spots of light I referred to earlier are simply water ice that sunlight is reflecting upon, giving it a shiny, spotted look.

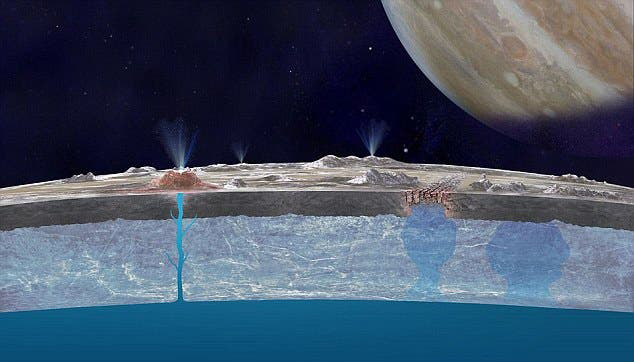

The last moon I will discuss, next to Callisto, is Jupiter’s fourth largest moon, Europa. Europa is made up of water ice, and it is speculated that it contains an ocean beneath its icy surface. If you look up a picture of Europa, you’ll quickly notice the almost “claw marks” spread across its surface—almost bloody looking scars and veins seen on the surface. These marks are due to the fracturing of the icy surface, tectonic activity, and the immense gravitational pull of Jupiter. What is most interesting about this satellite is that it has a real potential for life in its oceans. NASA’s Europa Clipper mission, launched on October 14, 2024, is being sent to investigate the moon. The goal of the mission is to determine if Europa has the right conditions to support life. This mission, projected to be finished in 2030, may just prove that we are not the only ones in our solar system.

Although, as we all know, it is unlikely there is an aquatic race of human-like beings on Europa, but it could still contain life as we know it—possibly humongous sea creatures that have evolved to withstand the harsh conditions on Europa, sea creatures that you would see in your nightmares. It’s an interesting and potentially unsettling line of thought to go down, realizing that we may not be alone in the Universe, much less our own solar system.

I step away from the telescope and look up at the star-like Jupiter. I feel honored to have been able to look at our largest planet, Jupiter, for the first time. I employ all of you to look at the sky with a telescope (weather permitting) if you ever have the opportunity. It really is an experience, to say the least. It made me feel much more connected to the universe, being able to see such a distant object. To know that somewhere out there in the sky, there is something going on that is beyond me. Bigger than me. Our problems seem small compared to a mass such as Jupiter.

What I love about astronomy is being connected to something that is so distant. I may never be able to visit these distant objects myself, but I thank the Universe for giving me an opportunity to be a little closer to them.

Once again, thank you for reading, and I hope you learned something new today. If you have anything you want me to discuss in particular, please send me an email at del47sol@gmail.com. I hope to hear from you.

Europa and it’s possible interior ocean.

Jupiter and its Galilean moons (similar to what I see when looking through my telescope).