Look-UP

by Mitchell Tester, College Student

Christmas & Astronomy

Happy holidays and Merry Christmas, everyone! This really is a special time of the year. As it is the holiday season, and Christmas is right around the corner, I wanted to somehow bridge the connection between astronomy and Christmas.

Astronomical roots of the holiday season lead us all the way back to the Neolithic period, so around 10,200 BC. Observations of the winter season starting were found at sites like Newgrange in Ireland and Stonehenge in England. People even in ancient Rome celebrated, and, like the people in the Neolithic period, observed what is called the “Winter Solstice” in the later days of the month of December, much like we do today.

From a technical standpoint, the Winter Solstice is the shortest day of the year. It occurs when the Earth’s axis is tilted farthest away from the sun. Usually, this happens in the Northern Hemisphere around December 21st or 22nd. In the southern hemisphere, it is quite the opposite, as around this time, they experience their Summer Solstice. With the Winter Solstice occurring, the days will begin to be longer again. This had symbolic meaning for ancient people, as many astronomical events did back in that time. For most civilizations, the Winter Solstice was symbolic of death and rebirth, focusing on marking the end of the darkest part of the year and the return of the sun, in a sense. Solstice means “sun standing still.” When a solstice occurs, it appears as if the sun stays in one spot at its lowest point in the sky, before it starts to move higher again.

In ancient times, festivals took place to celebrate the Winter Solstice. Pagan winter festivals existed, like the Roman festival of Saturnalia or the Germanic festival of Yule. In the case of Rome, they feasted, gave gifts, and even illegal gambling became permitted. At the core of the festival was the election of the “King of Saturnalia,” who was the person to lead the festivities and encourage fun at the festival. At the Germanic festival of Yule, similar festivities happened, with a focus on the burning of a Yule log for up to 12 days, which symbolized the return of the sun after the Winter Solstice. Fast forward to 336 AD in the Roman Empire, it was the first Christmas celebration. Pope Julius first officially declared December 25th as the date for Christmas, all the way back in the 4th Century.

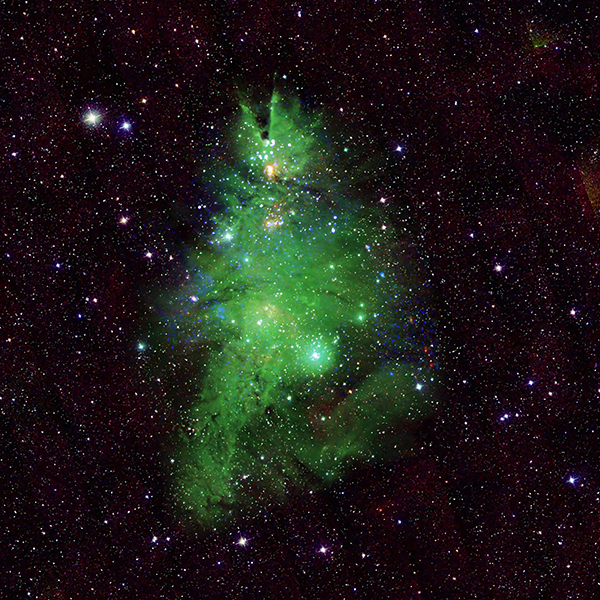

In the United States of America, one of the first recorded celebrations of Christmas was at Jamestown in 1607. In 1870, Christmas became a federal holiday in the United States. In recent years, Christmas and astronomy still coexist. The “Christmas Star” conjunction of Jupiter and Saturn back in 2020 showed us a rare conjunction of the two planets, making them appear as a very bright “star” in the sky. As this was right around Christmas, and brought the planets to appear closer than they had in nearly 800 years, it was dubbed the “Christmas Star.” More recently, as of 2023, NASA released striking images of a star cluster, some 2,500 light years away. They dubbed this cluster the “Christmas Tree Cluster” or its official name, “NGC 2264” (pictured above). The 14 stars in this cluster flicker due to gravitational lensing, making it appear like twinkling lights on a Christmas tree. Gravitational lensing occurs due to massive objects in space warping spacetime. The object’s light from the background of the curvature causes the light path to bend, and in the case of the Christmas Tree Cluster, distort. If you want to see this cluster for yourself, the winter months are a great time to do so. It can be found in the constellation of Monoceros, which is near the constellation of Orion and the red giant Betelgeuse.

Once again, everyone, happy holidays and Merry Christmas. I hope you all have a safe and fun time with family and friends.

Source: Nasa.gov

Space Facts

The Northern Lights

The Northern Lights, or aurora borealis, are caused by charged particles from the sun colliding with gases in Earth’s upper atmosphere. Earth’s magnetic field directs these particles to the poles, where they interact with gases like oxygen and nitrogen, creating a stunning light show. The colors of the aurora, such as green, red, blue, and purple, depend on the specific gas and altitude of the collision.