James Rada, Jr.

As an eighty-five-year-old man, it wouldn’t seem that Mark Strauss would be able to relate to modern teenagers. However, when he recently sat down before a group of students at Catoctin High School, Strauss didn’t tell them about his adulthood. He took them all the way back to 1941, when he was just a boy of eleven, living in Lvov, Poland.

“I was hunted to be killed, and almost my entire family and community were,” said Strauss.

He lived in a small three-room apartment with his parents and grandparents. When World War II started, his town came under control of the Soviet Union; however, in 1941, Germany attacked the Soviet Union and took control of Poland.

Strauss watched the German army roll into his town in their tanks and troop transports. The soldiers were all in high spirits, which shouldn’t be surprising since they were winning the war.

Yet, the next day, problems began. Strauss was walking on the street when he saw a mob of people attack a man and beat him to death.

“Two thousand people, mostly men, were killed in the next couple days,” recalled Strauss. “My uncle went for a walk on the street and never came back. Temples were torched, sometimes with people inside.”

These people were Jews, who made up about one-fifth of the town’s population. The Jewish community lived in fear as soldiers began going door to door, looking for Jewish citizens. Even if a Jewish family lied and said that they weren’t Jewish, there was always the possibility a neighbor would turn them in.

Jews were taken from their homes to be interrogated or simply shot on the street. Others were loaded into a truck and taken to a mass grave outside of the town, where they were shot.

“In one year’s time, almost all the Jews in my town had been murdered,” Strauss said. “My family—thirty to forty people—were killed, except for me and my parents.”

Strauss would hide himself from people to avoid the Nazis on the streets. His grandparents weren’t so lucky. He saw them being taken away, presumably to be killed, since he never saw them again.

Eventually Strauss’s luck ran out when a group of soldiers and local police broke into his family’s apartment. Strauss was there with his mother. His father was working at his job. The local policemen ransacked the apartment, looking for money.

“I was scared, because I knew I was going to die,” Strauss said.

Strauss and his mother probably would have been killed if one of the soldiers hadn’t found a picture of Strauss’s father in his Polish army uniform. The sight of the soldier in the picture changed the man’s mind about what he was doing, and he ordered his men to leave.

The remaining Jews in Lvov were eventually forced into a Jewish ghetto, an area of the city that was far too small a space, even for the few remaining Jews. Strauss and his parents had to share a room with twenty people. There was no greenery, no place to go to the bathroom, and little food and water.

A Catholic woman eventually wound up hiding Strauss in a 10 x 12 room for a year and a half.

“I was in jail, but a jail where you fear you could be executed every day and not just wait out your time,” said Strauss.

A jail it may have been, but it allowed him to survive, as the few remaining Jews in Lvov were killed or died from starvation. He still had little food, but at least he had a certain degree of safety. Strauss said he appreciated the family’s bravery in hiding him since he knew that they could have been killed for hiding him.

Strauss and the other Jews in Lvov were liberated by the Soviet Army in 1944. He moved to New York in 1947. He worked at MIT and became a painter and author. He also shares his story with groups like the students at Catoctin High School so that they can better understand what it was like during the Holocaust, and that something like that never happens again.

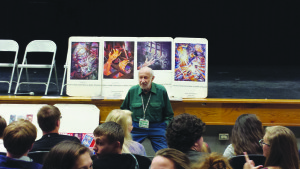

Holocaust Survivor, Mark Strauss, speaks with students at Catoctin High School about his personal experience and what it was like at that time in history.

Holocaust Survivor, Mark Strauss, speaks with students at Catoctin High School about his personal experience and what it was like at that time in history.

Photo by James Rada, Jr.