Great Maryland Gold Rush

Richard D. L. Fulton

The “Great Maryland Gold Rush,” which raged from the 1860s into the 1920s, petering out by 1940, was triggered by pure happenstance when gold was discovered there during the American Civil War.

Gold was reportedly discovered on a farm belonging to Samuel Ellicott, located near Brookville, Montgomery County, Maryland, during 1849; although, it apparently attracted little attention and was left largely unexplored.

One of the earliest newspaper reports of the find appeared in the January 31, 1849, edition of The Rockville Journal, in which it was stated, “Gold has been found on Mr. Ellicott’s farm in this county. It is thought there is an abundance of the metal there. A specimen was sent to the Philadelphia mint, which was pronounced genuine.” The story was reprinted in the February 2, 1849, edition of The (Boston) Liberator.

The sample submitted was more than likely a specimen mentioned in an article published in a February issue of the Howard Gazette, and reprinted in the February 5, 1849, edition of The (Baltimore) Sun, in which the Gazette stated “that a rock had been found on the farm which contained “a hundred dollars’ worth of gold.”

In today’s monetary evaluation, $100 would equate to $3,777, without taking the valuation of today’s value of gold per ounce into account. In the 1840s, gold was trading at about $18 per ounce. Today, gold can fetch $2,374 per ounce.

However, the actual amount of gold contained within the aforementioned rock was not given. But if the value of gold in the 1840s was at $18 per ounce, it would suggest by the $100 claim that the sample could have contained around 5.5 ounces. That 5.5 ounces of gold today could bring more than $13,000.

The rise in the interest in Maryland gold has generally been attributed to having been spurred by the discovery of gold at Great Falls, Montgomery County, Maryland, in 1861, a discovery directly tied to the advent of the American Civil War.

When Union troops were stationed at Great Falls on The Potomac River in 1861, Private McCleary (or McCarey) of the 71st Pennsylvania Regiment (or “1st California Volunteers”) was scrubbing skillets in the water for the camp cooks, when he recognized gold in the skillets, according to the C&O Canal Trust.

“After the war, he returned to the area, bought some farmland, and started mining for gold in Montgomery County,” C&O Canal Trust noted on its website. A particular Chesapeake and Ohio Canal National Historical Park wayside states that McCleary and some of his friends had only recovered around 11 ounces for their effort, which would have amounted to more than $26,000 in value.

McCleary’s find prompted a flurry in the establishment of gold mines, as investors sought to strike it rich in Maryland gold… leading to the first mine shaft sunk into Maryland soil in 1880.

By 1890, The (Baltimore) Sun reported in its February 24 issue, “The development of the mining industry in Montgomery County has made remarkable progress within the last six months, and there are no less than six mines being actively operated.” The newspaper identified the owners of the half-dozen mines as the Huddlestone mine, the Potomac Mining Company, the Iowa Mining Company, and by a number of private individuals.”

In 1900, the Maryland Gold Mining Company was formed, and the Great Falls Gold Mining Company was created in 1903 or 1904, according to the United States Geological Survey (Bulletin 1286). The Maryland Gold Mining Company folded in 1908. Following the closure of the Maryland Gold Mining Company, the site was reopened and operated under several guises, the last of which was called the Maryland Mining Company.

By 1910, gold recovery increased in interest, but The Sun reported that the layers containing the gold could be elusive and “unevenly distributed,” to the degree that profits had not lived up to expectations. “The value of the output of gold in Maryland is very variable,” the newspaper reported, adding, “It has reached as much as $25,000 annually, while in other years none has been produced.”

Most of the gold mines at this point in time, The Sun reported, were located “near the southern edge of Montgomery County near the Great Falls of the Potomac.”

By the 1930s, the quest for gold continued to decline in productivity. The Sun reported on August 4, 1935, “The annual production of gold in Maryland has been $71,583, virtually all of which was produced prior to 1906.”

By 1935, gold finds were reported all the way into Frederick County near Frederick City and in Braddock Heights. Six gold mines (actually, multi-commodity mines, of which one commodity included gold) were established in Frederick County. All told, gold was eventually reported in half a dozen Maryland counties. However, many of these reported finds did not result in the development of mines.

By 1940—when the last commercial gold mining company ceased operation—more than 45 gold mines had been dug in Maryland. In the course of less than 100 years, the total gold production of all the mines combined amounted to some 5,000 ounces. On today’s market, that would only have amounted to about $1,000,000.

The Sun, in 1935, almost forecasted the causations of the end of commercial gold mining operations in the state when it reported that the gold production business had sustained increasing costs of recovery, the result of the spotty occurrence of the gold and the hardness of the host rocks, which increased wear-and-tear on the equipment.

So where did the gold come from? According to the United States Geological Survey, mined gold in Maryland came from the Wissahickon Formation, basically layers of 750-million-year-old schists, gneisses, metagraywackes, and metaconglomerates (for the uninitiated, these are [metamorphic] rocks that were formed from other types of rocks as the result of re-crystallization from excessive heat and pressure exerted [normally] as a by-product of continental collisions).

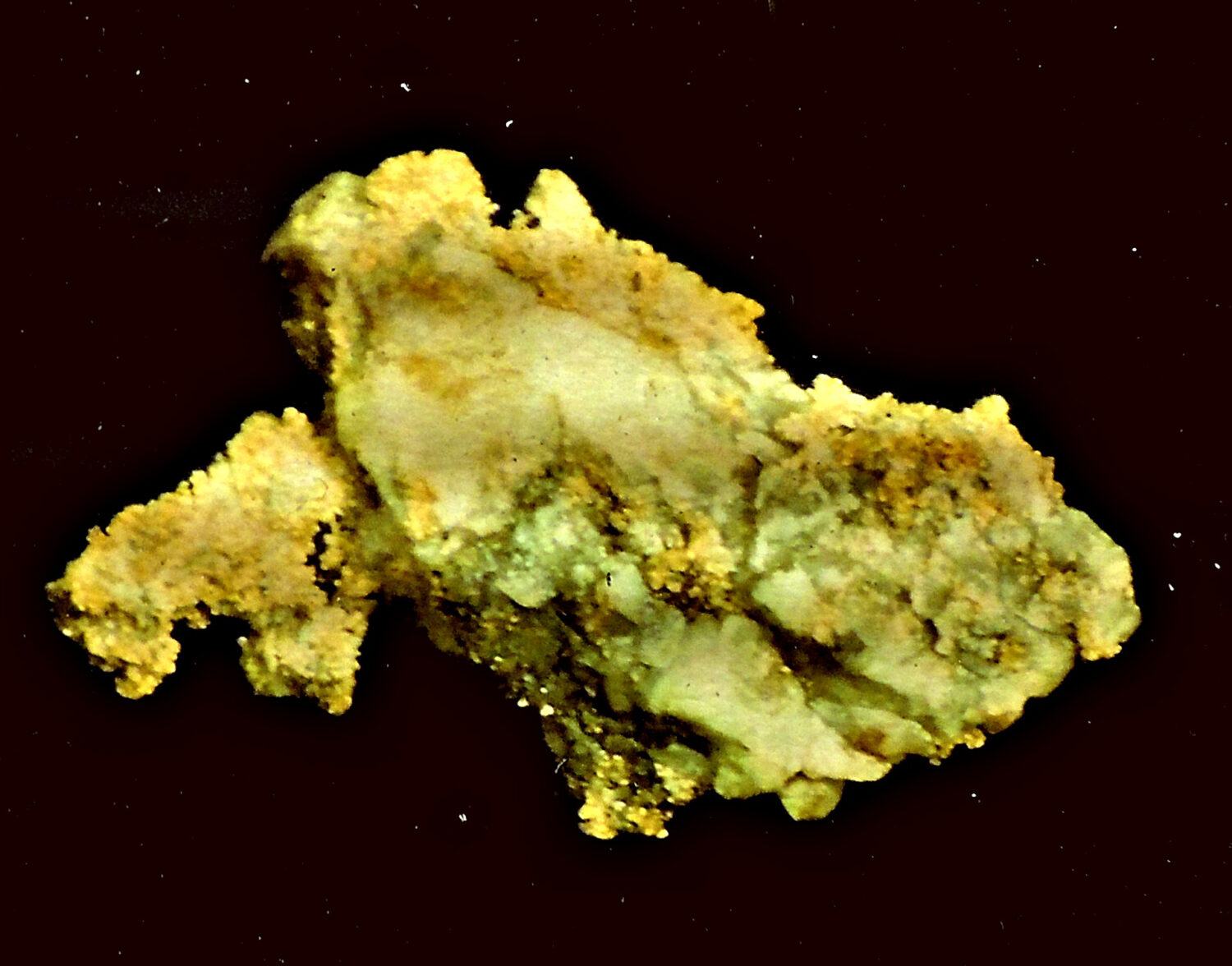

In these “reformed” rocks, gold tends to occur in veins, usually in quartz veins, which was injected into the various altered rocks when the quartz was still in liquid form.

Free gold (obtained by other means, such as “panning” for gold) occurs as grains, flakes, or nuggets. Most frequently, they are encountered in rivers or streams, where they eroded out of gold veins or from mine tailings (debris from former gold mines).

Basic equipment needed for panning for gold would be a pan; it can even be plastic. Steel is not recommended because it can rust. A small plastic see-through vial or bottle will also be needed to keep any gold or suspected gold in as one finds it. Other equipment one might need includes a shovel, pick, trowel, bucket, screen, and suction tweezers. Panning kits are also available online, which would include almost all of the essential tools.

Next, you would need a geological map in order to locate where any metamorphic rocks are located.

For those possibly interested in searching for gold in Maryland, according to the Maryland Geological Survey (Gold in Maryland, by Karen R. Kuff, 1987), Maryland has strict property rights laws, and panning and prospecting must be done with permission from the property owner.

Collecting of rocks is prohibited on state- and federal-owned lands unless permission is obtained from the appropriate agencies.

For additional information on panning for gold, recommended is the Maryland Geological Survey website at mgs.md.gov/geology/gold_resources.html.

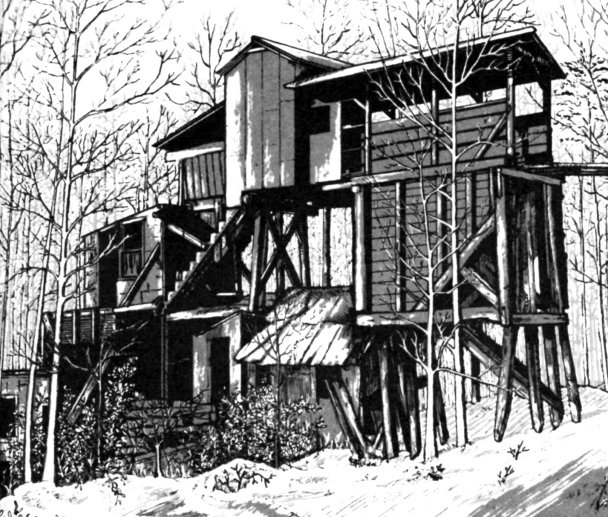

Ruins of Maryland’s abandoned gold mine.

Large multi-inch vein gold from Maryland mine.