The Evolution of Route 40

Richard D. L. Fulton

President Dwight D. Eisenhower established the International Highway System (IHS) when he signed the National Interstate and Defense Highways Act in 1956, which then initiated the creation of a highway system, connecting the East and West coasts.

Eisenhower, while serving in the Army, was initially inspired to create such a road system when, in 1919, he attempted to see how long it would take for a military unit to travel from the East Coast to the West Coast.

The convoy stalled at the covered bridge that crossed Tom’s Creek in Emmitsburg, forcing the column of motor vehicles to disperse and find alternative ways that would allow it to get around the Emmitsburg Bridge.

However, the vision of creating an east-west highway system predated Eisenhower’s vision by 150 years and was known as the National Road.

The National Road

The possibility of creating a road system connecting the East Coast with the Western states was initially conceived by President George Washington, and (subsequent president) Thomas Jefferson, both of whom, according to the U.S. Department of Transportation (DOT), had “believed that a trans-Appalachian Road was necessary for unifying the young country.”

Congress officially launched the proposed project in 1806 when it authorized the funds to be spent that would allow the work to begin. The bill was signed into law legislation, establishing the National Road by President Jefferson, making the venture “the first highway built entirely with federal funds,” According to the National Park Service (NPS).

Work on the National Road commenced in 1811; the first contract was awarded, and the first 10 miles of road were built, according to the U.S. Highway Administration. In building the road, the planners followed routes that had been pre-established by Native American trails, and they created new roadways that tended to be “paralleled by the military road opened by George Washington.”

What would turn out to be the first leg of the proposed National Road was to be constructed from the Potomac River, Cumberland, to the Ohio River.

During 1818, the National Road reached Wheeling (then in Virginia) on the Ohio River, successfully linking the Ohio River to the Potomac. This portion of the National Road is also known as the Cumberland Road. The Cumberland to Wheeling stretch of the National Road was the second road in the country that was paved with macadam (layering and compacting crushed stones) which was applied to the National Road in 1834.

Subsequent construction pushed the National Highway to Ohio and Indiana, reaching Illinois in 1834, “where construction ceased due to a lack of funds,” even though Congress had authorized its extension into Missouri, according to the NPS and the DOT. Sections of the new road were comprised of a mix of toll roads and turnpikes.

However, the highly successful road fell onto hard times, not only running out of money for further construction in 1834 but also faced reduction in use as the result of high-maintenance costs and the rise and expansion of railroad infrastructures.

Nevertheless, from about 1910 into the 1920s, the use of the National Road saw a renewed surge with the development of and the increased ownership of automobiles, which provided for greater public mobility and reduced reliance on railroads, according to the DOT.

In 1929, the National Road became part of U.S. Route 40, which ultimately stretched from Atlantic City to San Francisco, until U.S. Route 40 was truncated in Utah when U.S. Route 80 took over the route from Utah to the West Coast. The entire east-west highway system was ultimately superseded in the 1950s when Eisenhower’s Interstate Highway System was created.

Maryland Route 40

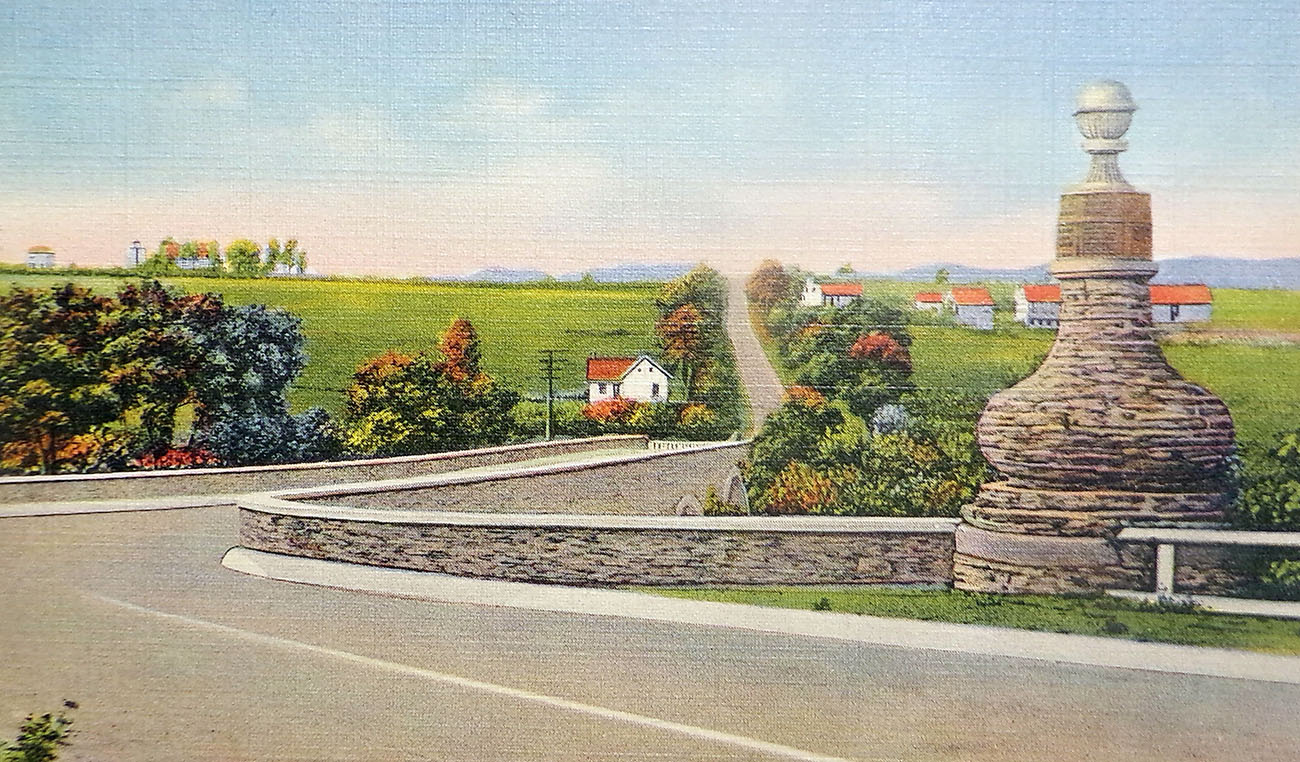

Today, basically two versions of U.S. Route 40 exist. The older version is referred to as Route 40 Alternate, while the newer version is simply referred to as U.S. Route 40. These two sections were cut off from their inclusion in Route 40 when the Interstate Highway System was developed in 1956. Route 40 Alternate consists of two sections, which deviate from the present course of U.S. Route 40 and follow the original routes of the old National Road (as it existed when it was redesignated as Route 40). The two sections are referred to as the National Pike, preserving its relationship with the old National Road.

One of the two Route 40 Alternate sections runs between Keysers Ridge and Cumberland, and is 31.80 miles in length. This section of Alternate Route 40 serves as the main street through Grantsville and Frostburg, according to Wikipedia (“U.S. Route 40 Alternate (Keysers Ridge–Cumberland, Maryland“).

According to Wikipedia (“U.S. Route 40 Alternate (Hagerstown–Frederick, Maryland)“), the second section runs from Hagerstown to Frederick, and is 22.97 miles in length, and passes through Funkstown, Boonsboro, Middletown, and Braddock Heights.

Because both sections of Route 40 Alternate traverse sections of the former old National Road, by happenstance, they offer scenic views and travel through historic areas of the towns they pass through. For example, the last remaining highway toll-gate house can be seen in LaVale.

U.S. Route 40 in Maryland is a major east-west highway that stretches from Garrett County to Cecil County in the northeast, and, being 220 miles in extent, constitutes it as being the longest highway in Maryland.

The highway transverses nine Maryland counties, including Garrett County, Allegany County, Washington County, Frederick County, Carroll County, Howard County, Baltimore County, Harford County, and Cecil County.

To make matters as confusing as possible to explain, as U.S. Route 40 crosses the state of Maryland, it shares roadways with other highways. From Keysers Ridge and Hancock, U.S. Route 40 cojoins Interstate 70, separating from that route along the Potomac, and proceeding on its own, until it merges with U.S. Route 15 in Frederick, and continues cojoined with U.S. Route 70, and subsequently continues as U.S. Route 40 through Baltimore to the state line, according to East Coast Roads (eastcoastroads.com) and others.

The “Golden Mile”

As U.S. Route 40 West passed through Frederick, it spawned a two-mile section of corridor, which became the focus of economic development for Frederick, and hence, was dubbed the “Golden Mile,” which was most likely due, in part, because the route from Frederick led directly to Baltimore.

According to the Golden Mile Alliance, the U.S. Route 40 passage through Frederick began to attract economic development, beginning in the early 1930s.

The corridor continued to attract commercial investment, which was further fueled by the creation of U.S. Route 15 in the 1950s.

Today, according to businessinfrederick.com, the Golden Mile, which has come to be further regarded as the gateway into the city,” the Golden Mile experiences “an average daily traffic volume of nearly 50,000 vehicles.” Golden Mile Alliance reported that, “The Golden Mile makes up over 50 percent of the commercial land within The City of Frederick.”

Having suffered through an economic slump around 2000 due to business bankruptcies and other issues, the corridor did successfully rebound as the result of Golden Mile marketing campaigns, and in 2018, this corridor was designated by the State of Maryland as an “Enterprise Zone.” For additional information on the Golden Mile, visit the Golden Mile Alliance website at goldenmilealliance.org.