by James Rada, Jr.

1871 — Catoctin County, Maryland

Can you imagine a Catoctin County, Maryland? It would have included Frederick County, north of Walkersville, and Mechanicstown would have been the county seat.

It was a dream that some people in the northern Frederick County area pursued throughout 1871 and 1872. The Catoctin Clarion was only on its tenth issue when it carried a long front-page article signed with the pen name Phocion. Phocion was an Athenian politician, statesman, and strategos in Ancient Greece.

The issue had been talked about within groups of people for a while, and it was time to garner support by taking the issue to a larger, general audience.

“Some sober sided citizens in our valley are quietly discussing the question among themselves, shall Frederick county be divided and the new county of Catoctin be erected into a separate organization?” the newspaper reported. Wicomico County had been formed in 1867 from portions of Somerset and Worcester counties, so the idea of another new Maryland county was not far-fetched. In fact, Garrett County would be formed from the western portion of Allegany County in 1872.

The main reason put forth for creating a new county was the distance and expense of traveling to Frederick to register deeds and attend court. Opponents argued that creating a new county would be costly for the citizens in the new county. New county buildings would have to be constructed and county positions filled. All of this financial burden would have to be absorbed by the smaller population in the new county.

“Our neighbors across the Monocacy in the Taneytown District have but a short distance to go to attend Carroll County Court. Why shall we on this side be deprived privileges which were granted to them? Shall the people on one side of the Monocacy be granted immunities which are to be withheld from citizens residing on the other side?” the Clarion reported.

Besides northern Frederick County, Phocion said that in Carroll County, residents of Middleburg, Pipe Creek, and Sam’s Creek were also interested in becoming part of Catoctin County.

“If a majority of the citizens residing in Frederick, Carroll, and Washington counties (within the limits of the proposed new county) favor a division, I see no reason why it should not be accomplished,” the newspaper reported.

In deciding on what the boundaries of the new county would be, there were three conditions that needed to be met in Maryland: (1) The majority of citizens in the areas that would make up the new county would have to vote to create the county; (2) The population of white inhabitants in the proposed county could not be less than 10,000; (3) The population in the counties losing land could not be less than 10,000 white residents.

Interest reached the point where a public meeting was held on January 6, 1872, at the Mechanicstown Academy “for the purpose of taking the preliminary steps for the formation of a New County out of portions of Frederick, Carroll and Washington counties,” the Clarion reported.

Dr. William White was appointed the chairman of the committee, with Joseph A. Gernand and Isaiah E. Hahn, vice presidents, and Capt. Martin Rouzer and Joseph W. Davidson, secretaries.

By January 1872, the Clarion was declaring, “We are as near united up this way on the New County Question as people generally are on any mooted project—New County, Railroad, iron and coal mines, or any other issue of public importance.”

Despite this interest in a new county, by February the idea had vanished inexplicably from the newspapers. It wasn’t until ten years later that a few articles made allusions as to what had happened. An 1882 article noted, “It was to this town principally that all looked for the men who would do the hard fighting and stand the brunt of the battle, for to her would come the reward, the court house of the new county. The cause of the sudden cessation of all interest is too well known to require notices and only comment necessary is, that an interest in the general good was not, by far, to account for the death of the ‘New County’ movement. Frederick city, in her finesse in that matter, gave herself a record for shrewdness that few players ever achieve.”

A letter to the editor the following year said that the men leading the New County Movement had been “bought off, so to speak, by the promises of office, elective at the hand of one party, appointive at the hands of the other, and thus the very backbone taken out of the movement.” The letter also noted that the taxes in Frederick County were now higher than they had been when a new county had been talked about, and that they wouldn’t have been any higher than that in the new county. “And advantages would have been nearer and communication more direct,” the letter writer noted.

My name is Honshuu (pronounced hon shoe), which means “trouble” in Japanese. Why in Japanese? Because I am a Shiba Inu mix, one of six ancient dog breeds from Japan. We were bred for hunting and flushing out small game. Some say we have cat-like agility; I like to say I move like a ninja! Speaking of cats, we do get along well with them—they are fun to chase.

My name is Honshuu (pronounced hon shoe), which means “trouble” in Japanese. Why in Japanese? Because I am a Shiba Inu mix, one of six ancient dog breeds from Japan. We were bred for hunting and flushing out small game. Some say we have cat-like agility; I like to say I move like a ninja! Speaking of cats, we do get along well with them—they are fun to chase. “Some days I wonder if it’s a blessing or a curse to live to be as old as I am,” said

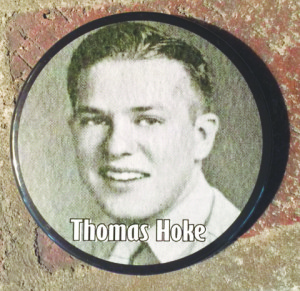

“Some days I wonder if it’s a blessing or a curse to live to be as old as I am,” said Emmitsburg native and ninety-two-year-old World War II Veteran, Tom Hoke. “I’ve lived plenty of good times and plenty of bad times. I hope, when it’s my time to go, that I go without being a burden on anyone.”

Emmitsburg native and ninety-two-year-old World War II Veteran, Tom Hoke. “I’ve lived plenty of good times and plenty of bad times. I hope, when it’s my time to go, that I go without being a burden on anyone.”